Anaemia in India

India has higher than expected levels of anaemia. Could measurement be part of the explanation?

Over half of all women, and two-thirds of children under the age of five in India are anaemic. India's high rates of anaemia are something of a puzzle in global health because while many other indicators of nutritional outcomes have improved over time, India's anaemia numbers appear to have worsened.

What is anaemia?

Anaemia is a condition in which the blood has less haemoglobin[1] than normal which reduces the capacity of the blood to carry oxygen through the body. This results in fatigue and dizziness that can lower the capacity to grow, develop and work, and in more severe cases can cause significant cognitive and physical impairment. Anaemia in women also raises the risk of death for mothers and children during or soon after birth, as well as the risk of babies being born too early or too small. Anaemic mothers are more likely to have anaemic children.

Anaemia is classified as being mild, moderate or severe based on the extent of haemoglobin deficiency.[2] The majority of anaemia in India is categorised as mild or moderate with under 3% of women and children being reported as severely anaemic. However even mild and moderate anaemia if left untreated can lead to serious long term health consequences[3].

Anaemia prevalence in India

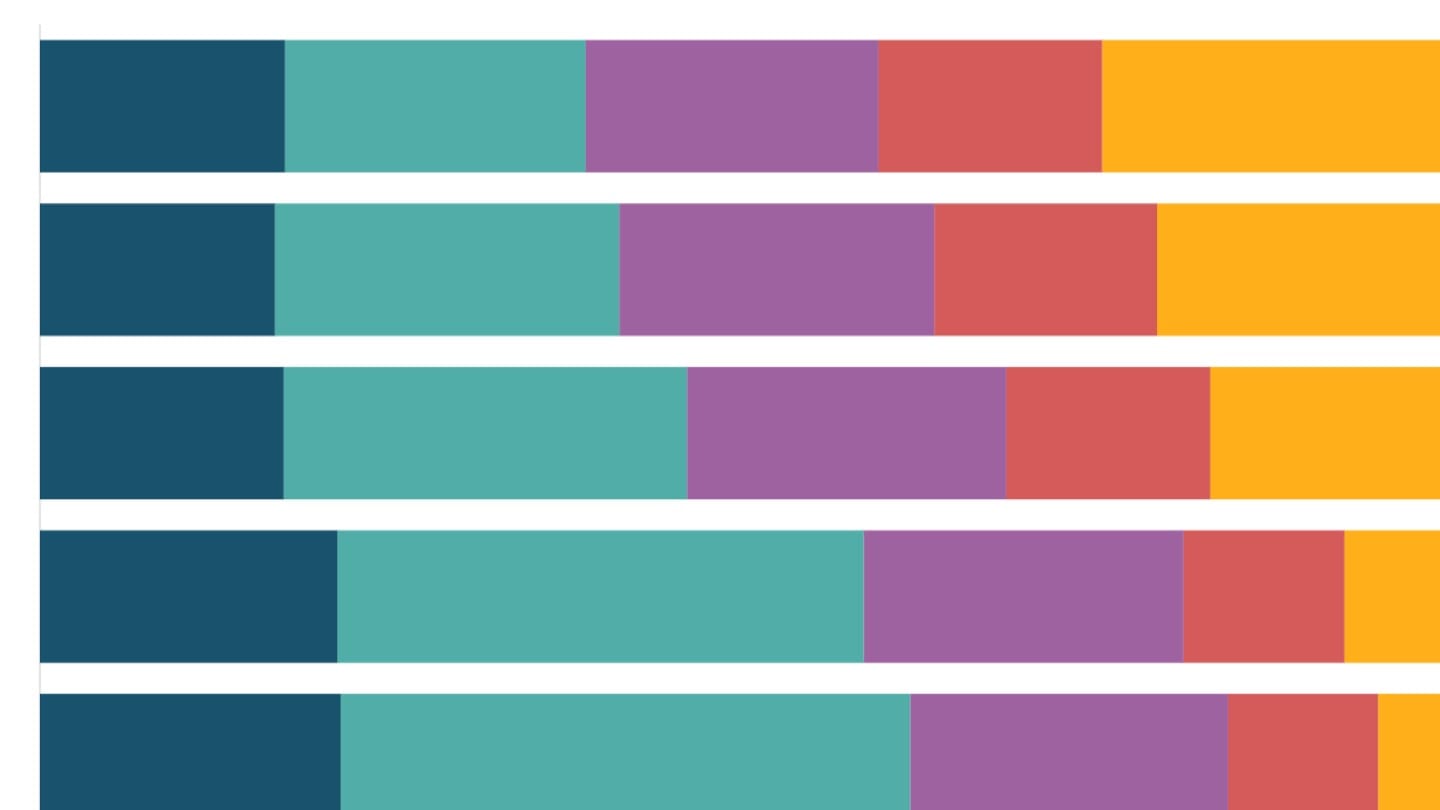

The most recent data for anaemia in India comes from the National Family Health Survey's fifth round conducted in 2019-21[4]. This data shows that two in three children under the age of five were anaemic, as well as over half of women and a quarter of men aged 15-49 years.

While some of India's poorest states including Bihar and Odisha have high rates of anaemia among women and children, the prevalence is not restricted to poor states alone; Gujarat has the highest incidence of anaemia in children, and West Bengal among women.

Poorer women are more likely to be anaemic. The prevalence of anaemia declines as the mother's schooling and household wealth increase. However, even within the richest 20% of Indians, over half of women aged 15-49 are anaemic.

Why does India have such high levels of anaemia?

One key cause of anaemia is iron deficiency. Iron is a key component of haemoglobin, and iron deficiency is estimated to be responsible for half of all anaemia globally[5]. The onset of the menstrual cycle and childbirth, both involving the loss of blood, are particularly associated with iron deficiencies in young women.

Although the quality of diets and the absence of iron-rich foods from vegetarian diets is often thought to be a likely cause of anaemia, researchers have found no direct link between vegetarianism and anaemia. Once income levels, location, caste and other variables were controlled for, they found that vegetarians were not more likely to be anaemic[6].

Over the last few decades, government programmes to distribute iron supplements to pregnant women and those with newborns have expanded, but not all women take the supplements throughout their pregnancies. While the share of Indian women who took iron and folic acid tablets during the pregnancy for their most recent birth is now up to nearly nine in ten women, only one quarter took these supplements for six months. Richer and better educated women were more likely to have taken iron and folic acid tablets for at least 100 days during their pregnancies[7].

However, the extent of anaemia that is caused by iron deficiency alone has not yet been conclusively established in India - other causes include infections like malaria and parasitic infections. The 2016-18 Indian national survey[8] of children and adolescents found that even though the levels of iron deficiency were higher among richer children, the levels of anaemia were higher among poorer children. This suggested that poorer children were perhaps relatively less able to utilise the iron in their bodies to form haemoglobin as a result of infections and deficiencies[9].

Does measurement matter?

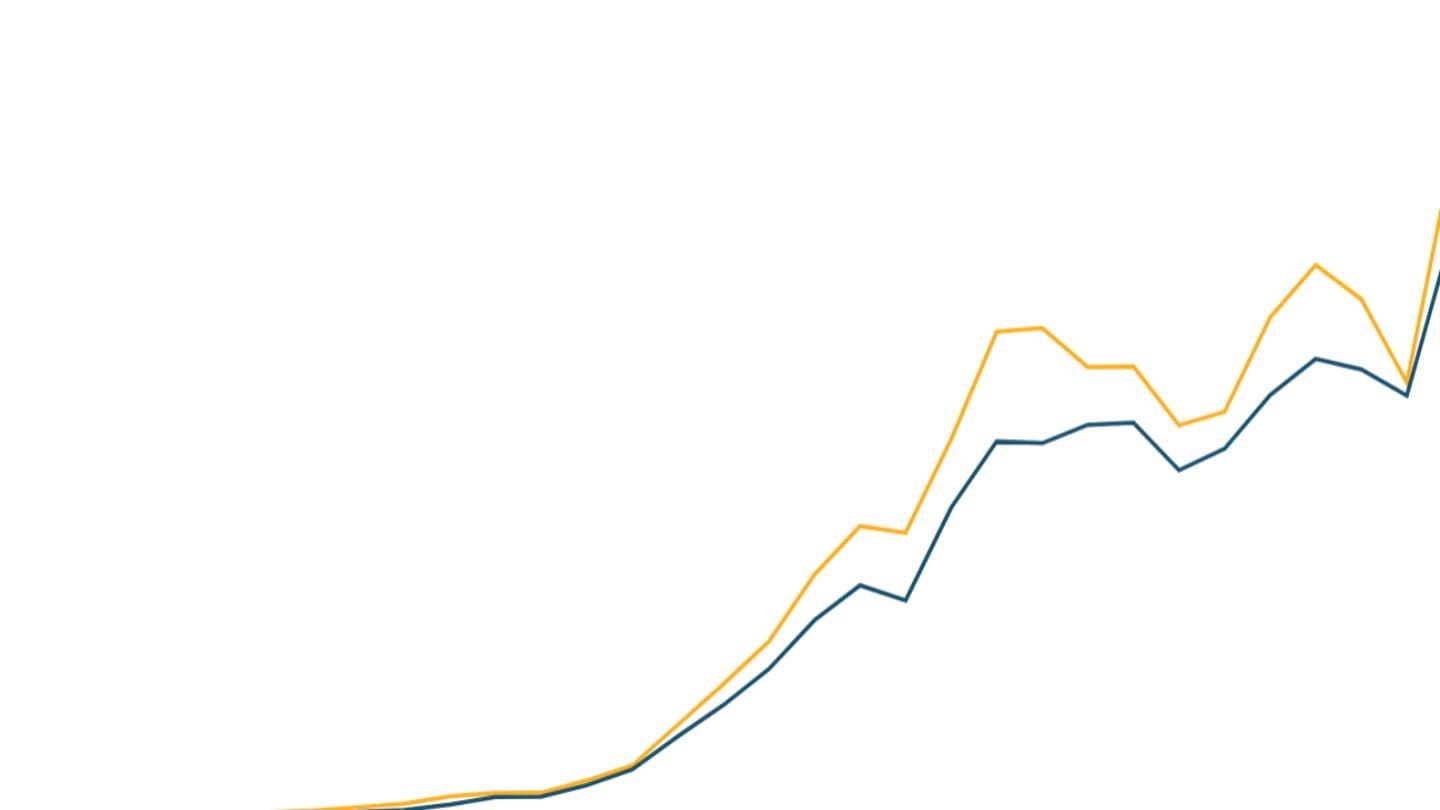

Not just are India's anaemia numbers high, NFHS data also suggests that the prevalence of anaemia in India rose between 2015-16 and 2019-21, the two most recent rounds of the survey. These are surprising numbers; during this same period the share of children and adults who are stunted, or the share of children and adults who receive adequate nutrition, for example improved.

Could India's high (and apparently growing anaemia numbers) have something to do with the way anaemia is being measured?

Data on anaemia comes from India's National Family Health Surveys which are part of a system of national representative household health surveys conducted in over 100 countries across the developing world.

Data on anaemia for India and many developing countries comes by using what is called the capillary method, where the health surveyor pricks the respondent's finger to collect blood. This is a method that is easy to conduct without the need for sophisticated equipment, transport or highly trained staff - a hand-held device allows for on-the-spot results.

Haemoglobin levels can also be measured through the venous method (blood collected from a vein or artery) that some other countries use. Given that it is a more invasive method requiring skilled staff and lab analysis within hours, it is currently used in more developed countries.

There is evidence to suggest that the venous method produces lower estimates of anaemia especially among children, and that the capillary method that India uses produces higher and less reliable estimates, as one recent systematic review suggests[10]. In Tanzania, for instance, simultaneous haemoglobin testing using both methods on similar groups found that the prevalence estimate for anaemia was 12 percentage points lower in the venous blood sample (47%) than in the capillary blood sample (59%) among children aged 6-59 months. The difference was smaller yet still significant for women (5 percentage points lower in the venous than in the capillary blood sample)[11].

In India, a study that used a 2016-18 government survey of children and adolescents that used the venous method for testing found significantly lower levels of anaemia than the NFHS had for the same groups[12].

Whether one of these methods systematically produces higher or lower estimates of anaemia is now an important question in public health - in 2023 the WHO for instance called for a systematic review of the available evidence[13] and the Indian government is experimenting with a new survey using the venous method[14].

What can we say about anaemia in India?

For the most part, richer groups and countries have better health outcomes, including on anaemia, but India's anaemia levels are notably high in relation to with comparable countries[15]. India and Rwanda both conducted similar household surveys that collected data on anaemia using the capillary method at a similar time. Despite Rwanda's per capita income being less than half India's, the rates of anaemia among both women and children were higher in India. Rwanda also seemed to see a faster decline in anaemia prevalence over time.

Comparing countries that collect data on anaemia through the venous method with those using the finger-prick method may not be sound. But what we can say about India is that its levels of anaemia as measured through the capillary method are significantly higher than some countries that use the same method, even though they are much poorer.

[1] Protein in the blood that carries iron

[2] In India's National Family Health Survey, the levels of anaemia are defined as follows:

Levels for children: Mild - 10.0-10.9 grams (g) of haemoglobin per deciliter (dl), moderate 7.0-9.9 g/dl, severe <7.0 g/dl

Levels for women: Mild - 11.0-11.9 g/dl, Moderate - 8.0-10.9 g/dl, Severe <8.0 g/dl

Levels for men: Mild - 12.0-12.9 g/dl, Moderate - 9.0-11.9 g/dl, Severe <9.0 g/dl

[3] India's official public health response is for children with mild and moderate cases to be treated with a supplement, follow-up by a health worker every 14 days and a blood test after two months. If her levels have not improved, the child should be referred to a hospital. For men, women and children, severe cases must be urgently referred to a healthcare provider

[4] This is a large nationally representative sample survey conducted by the International Institute of Population Sciences, and is released by the union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. The NFHS is part of the Demographic and Health Surveys, a set of standardised health surveys conducted in over 100 developing countries around the world

[5] Other causes of anaemia include malaria, hookworm and other helminths, other nutritional deficiencies, chronic infections, and genetic conditions.

[6] 'Stunting and Wasting Among Indian Preschoolers have Moderate but Significant Associations with the Vegetarian Status of their Mothers' (2020), Headey et al, The Journal of Nutrition

[7] National Family Health Survey 5 (2019-21)

[8] The Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey was a nationally representative survey of over 100,000 children and adolescents aged 0-19 conducted by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

[9] 'Childhood and Adolescent Anemia Burden in India: The Way Forward' (2022), Sachdev et al, Indian Pediatrics

[10] 'Associations between type of blood collection, analytical approach, mean haemoglobin and anaemia prevalence in population-based surveys: A systematic review and meta-analysis' (2022), Stevens et al, Journal of Global Health

[11] 'Anaemia Estimates using Venous and Capillary Blood Samples in the2022 Tanzania DHS-MIS' (2023), The DHS Program

[12] 'Childhood and Adolescent Anemia Burden in India: The Way Forward' (2022), Sachdev et al, Indian Pediatrics

[14] As a result of this and the global debate around the best way to measure anaemia, India's National Family Health Survey which used the capillary method will no longer collect data on anaemia, but a separate survey - the Diet and Biomarkers Survey in India (DABS-I) (to be conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) and the National Institute of Nutrition (NIN) and funded by ICMR, using the venous method - is likely to collect this data

[15] To ensure that we are comparing countries that use the capillary method with each other, we look at the 100+ countries surveyed through the Demographic and Health Surveys only. Within this group, we compare with countries that conducted a DHS around the time as India (2019-21).