Child stunting in India

Indian children are among the shortest in the world. While the rates of child stunting have declined over time, a substantial share of Indian children, especially in poorer states and among marginalised groups, are stunted

One of the most important measures of a country's nutritional and public health status is whether its children are adequately nourished. The most closely tracked indicator on child nutrition outcomes is stunting, or lower than expected height for age. More than a third of children under the age of five in India are stunted.

Height is not purely an outcome of a child's genes, but also of the nutrition that they receive before they are born, as well as in their early years. An undernourished child can be too short for their age, or stunted. Stunting in early life can lead to long-term challenges in health, physical and cognitive development, as well as learning and earning potential. Once the crucial early years have passed, research shows that catching up to standard height is unlikely without a dramatic improvement in the child's environment.[1]

Data on stunting in India comes from the National Family Health Surveys conducted by the International Institute for Population Sciences under the Ministry of Health and Welfare.[2] Data for other countries comes from the Demographic and Health Surveys system.[3]

Why is stunting a critical indicator of malnutrition?

A child is considered stunted if their height is significantly lower than the average for children of the same age and gender using World Health Organization growth standards.[4]

This variation from the average is calculated as the "Standard Deviation", and it tells us how far the child is from the average. If the child's height is more than two standard deviations below the WHO's median height for their age, it means the child is shorter than expected and is classified as stunted.

Child stunting is a crucial indicator, because it is a sign of poor nutrition over time and points to long-term malnutrition or frequent illness.[5] It can have long-term effects on health, physical and cognitive development, learning and earning potential.[6] For instance, studies show that stunted children are more likely to repeat grade in school[7] and less likely to land a job in the formal sector as adults.[8]

While genetics play a role in determining child heights, research shows that other factors play a crucial role as well. Birth order[9], the mother's health and social status, as well as living conditions including exposure to infections in early life as a result of poor sanitation, also shape the average height of the population.[10]

Decline in stunting over time

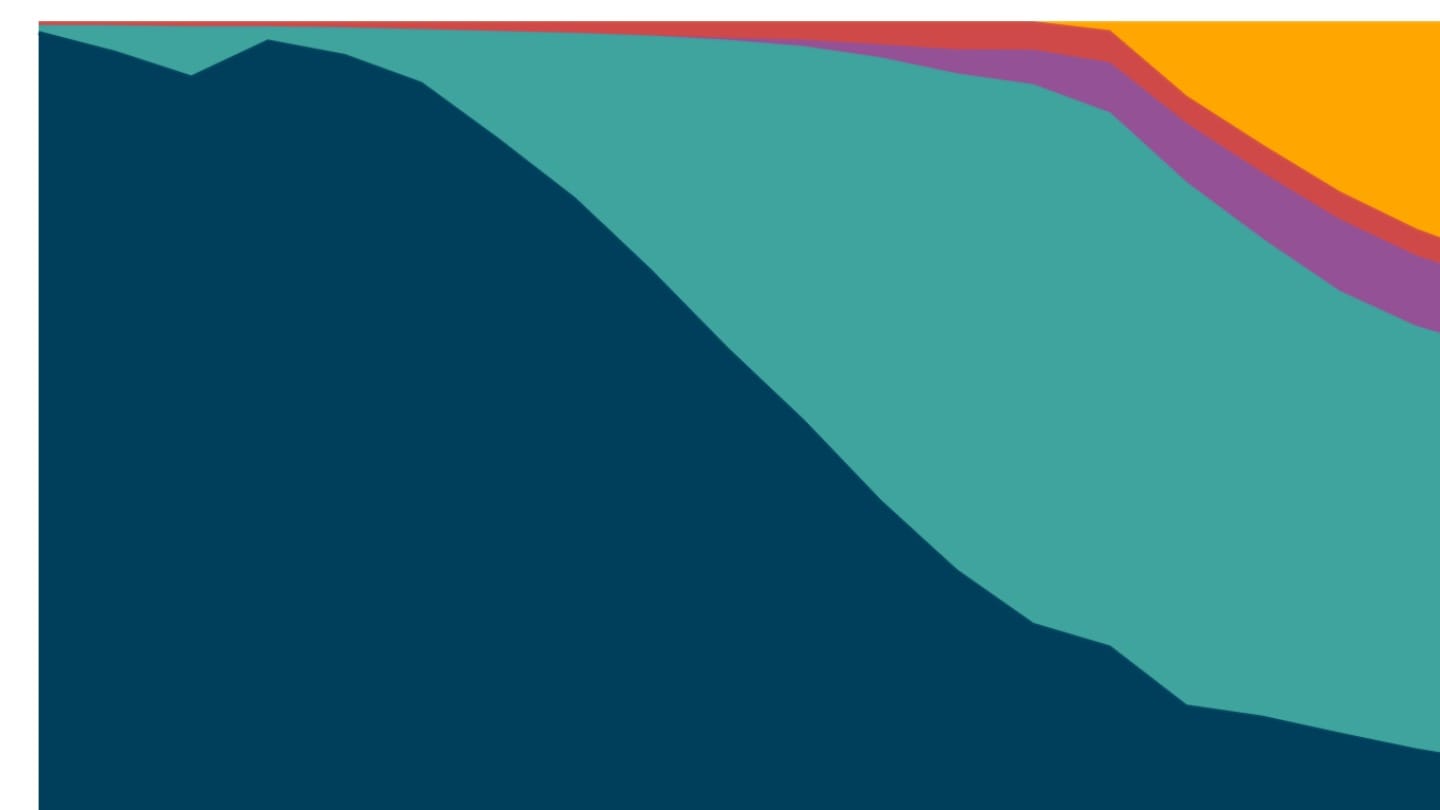

Child stunting in India has decreased over time; in 1993, more than one in every two children were stunted.

However, the levels of child stunting in India remain high and are comparable to those seen in Sub-Saharan African nations with much lower per capita incomes. Bangladesh had higher levels of stunting than India in the 1990s, but has lowered the prevalence of stunting among young children much faster in the last two decades than India.

Who is affected by stunting?

Within a country, differences in child height can signal deeper, persistent inequalities, particularly when malnutrition and infectious diseases are widespread.[11]

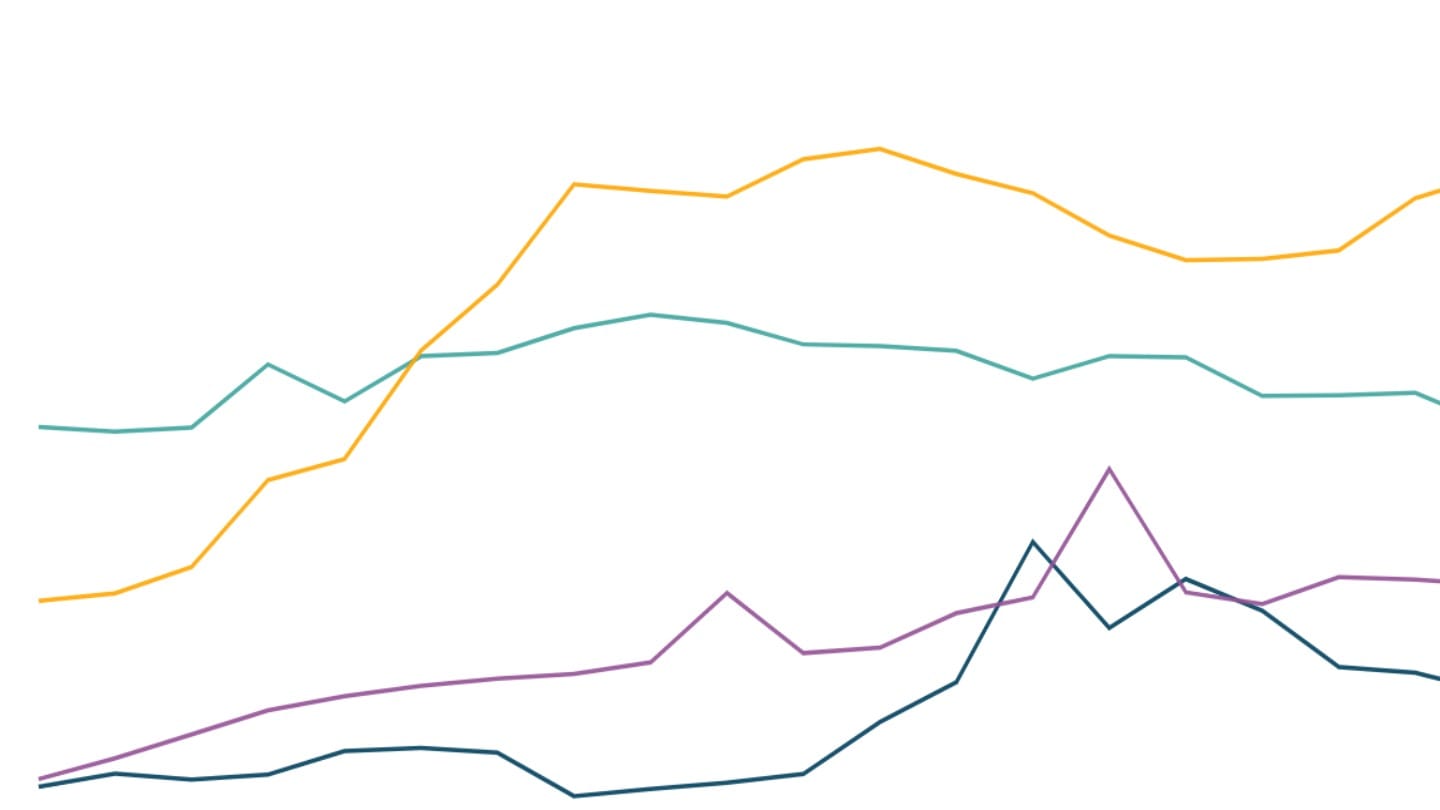

Stunting affects 30% of urban children, while the rate is higher in rural areas at 37%.[12] This urban-rural gap has not narrowed significantly over the last two decades. Across both sectors, children from the richest households are about half as likely to be stunted compared to those from the poorest households.

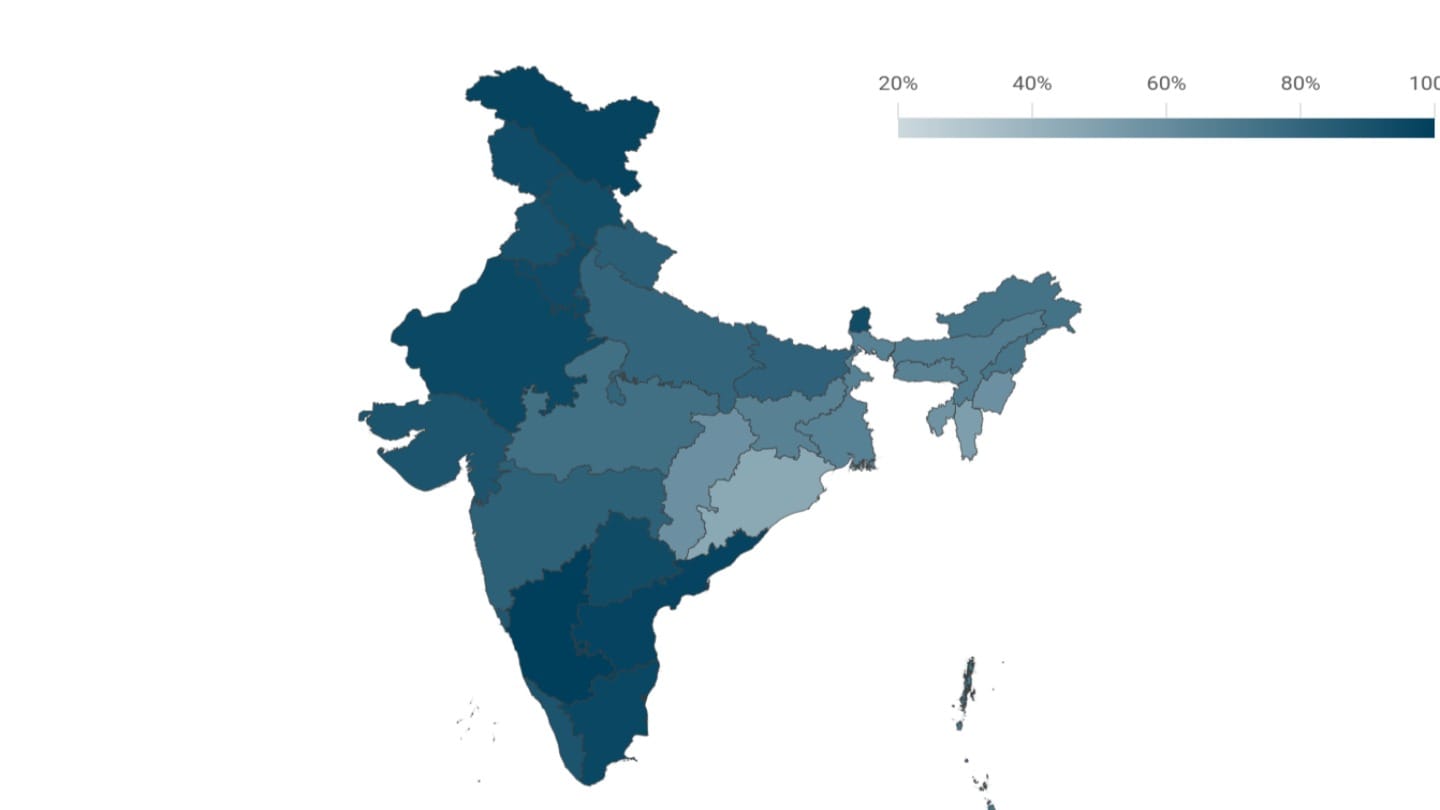

Among Indian states, the rates of stunting are highest in the poorest states - Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Jharkhand where about two in five children are stunted. These figures are comparable to some of the worst ranking countries globally, like the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola. While it is less prevalent in richer states like Kerala, Punjab and Tamil Nadu, about a quarter of children are stunted in these states as well. These are similar to levels seen in countries like South Africa, Myanmar and Malaysia.

The persistently high rates of stunting in India despite economic growth have led to some debate around the WHO's international growth standards, based on data from six countries, including India.[13] However, research suggests that the high rates of stunting in India reflect a complex combination of multiple underlying factors, rather than just issues with the standards themselves.

[1] Can Children Catch up from the Consequences of Undernourishment? (2020), Jef L Leroy et al, Advances in Nutrition.

[2] National Family Health Survey 2019-21, International Institute for Population Sciences.

[3] STATcompiler, Demographic and Health Surveys Program.

[4] WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study.

[6] Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey 2016-18.

[7] Stunting, age at school entry and academic performance in developing countries (2021), Gansaonré, Rabi et al, Acta Paediatrica.

[8] Early childhood length-for-age is associated with the work status of Filipino young adults (2009), Carba DB et al, Economics and Human Biology.

[9] Choice not genes - Probable cause for the India-Africa child height gap (2013), Seema Jayachandran, Rohini Pande, Economic and Political Weekly.

[10] Stunting among Children - Facts and Implications (2013), Diane Coffey, Angus Deaton, Jean Drèze, Dean Spears, Alessandro Tarozzi, Economic and Political Weekly.

[11] The Impact of Poverty and Discrimination on Child Height in India (2019), Diane Coffey, Ashwini Deshpande et al, Population Research Center (PRC), The University of Texas, Austin.

[12] National Family Health Survey 5.

[13] The WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study took place in the cities of Davis, California, USA; Muscat, Oman; Oslo, Norway; and Pelotas, Brazil; and in selected affluent neighbourhoods of Accra, Ghana and South Delhi, India. These countries were selected to ensure diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds. Other criteria like high socio-economic status and low population mobility were also taken into account.