Why has female labour force participation in India changed?

After being low by global standards for decades, and falling further since the mid 2000s, the share of Indian women who are in the labour force has increased. We examine the parts of the workforce and the economy where these changes have occurred.

India's female labour force participation rate (LFPR) - the share of women who are either working or looking for work - is low by global standards, and dropped further in the early 2000s. Historically, a majority of Indian adult women reported that they were attending to household duties and were not available for paid work. However, there has been a sharp rise in female labour force participation rates in the last five years. We look at historical and current data to understand what explains the fall and rise of Indian women participating in the "productive economy".[1]

Changes in labour force participation over time

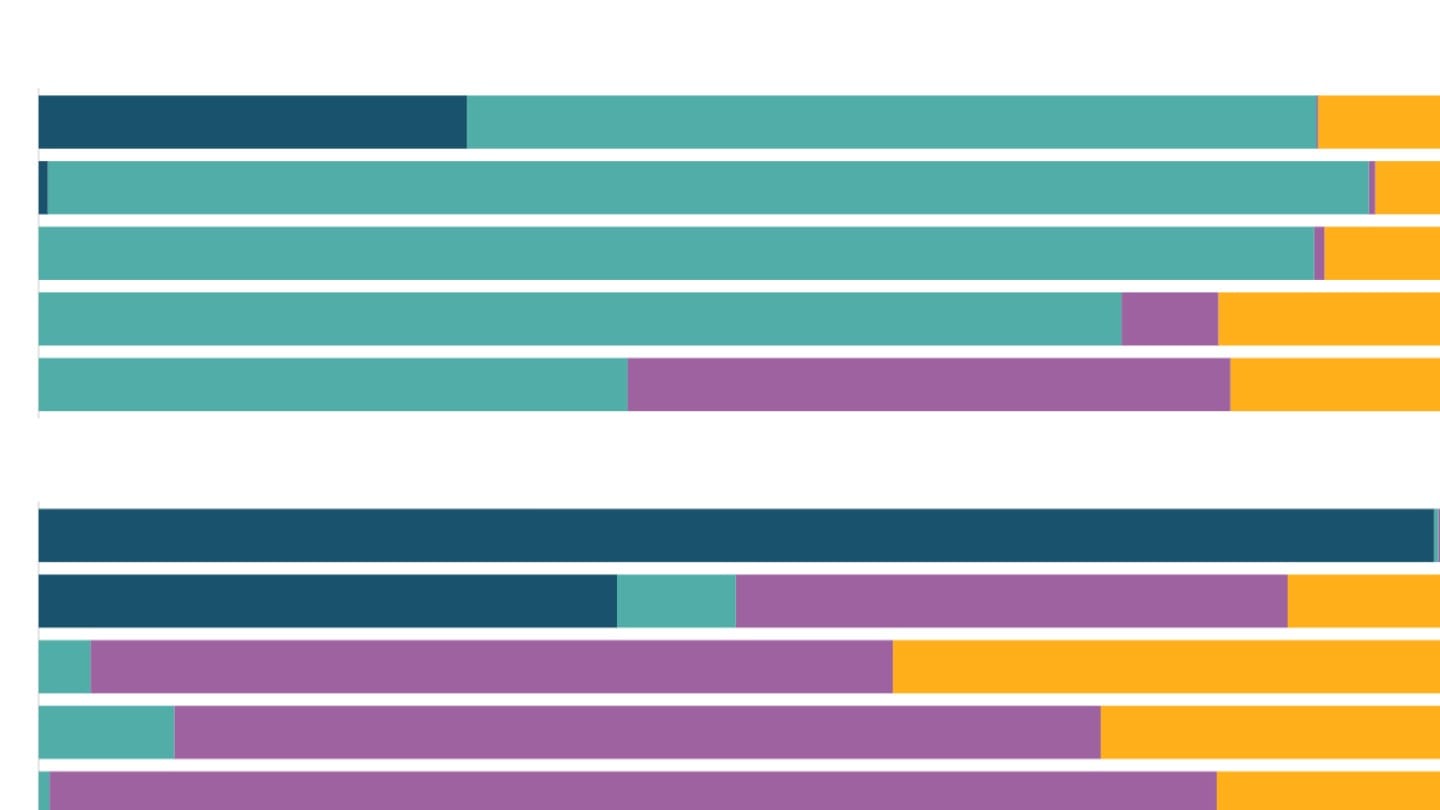

To understand long-term work patterns, we look at data on work over a longer reference period of one year. Here, workers are classified by the time spent on work in a particular area as "principal workers" (persons who worked in one activity for a relatively long part of the last 365 days), "subsidiary workers" (persons who worked for more than 30 days but less than six months on a particular activity), and "both principal and subsidiary workers" (those who worked for most of the year on one activity, and for a small part of the year on another activity).[2]

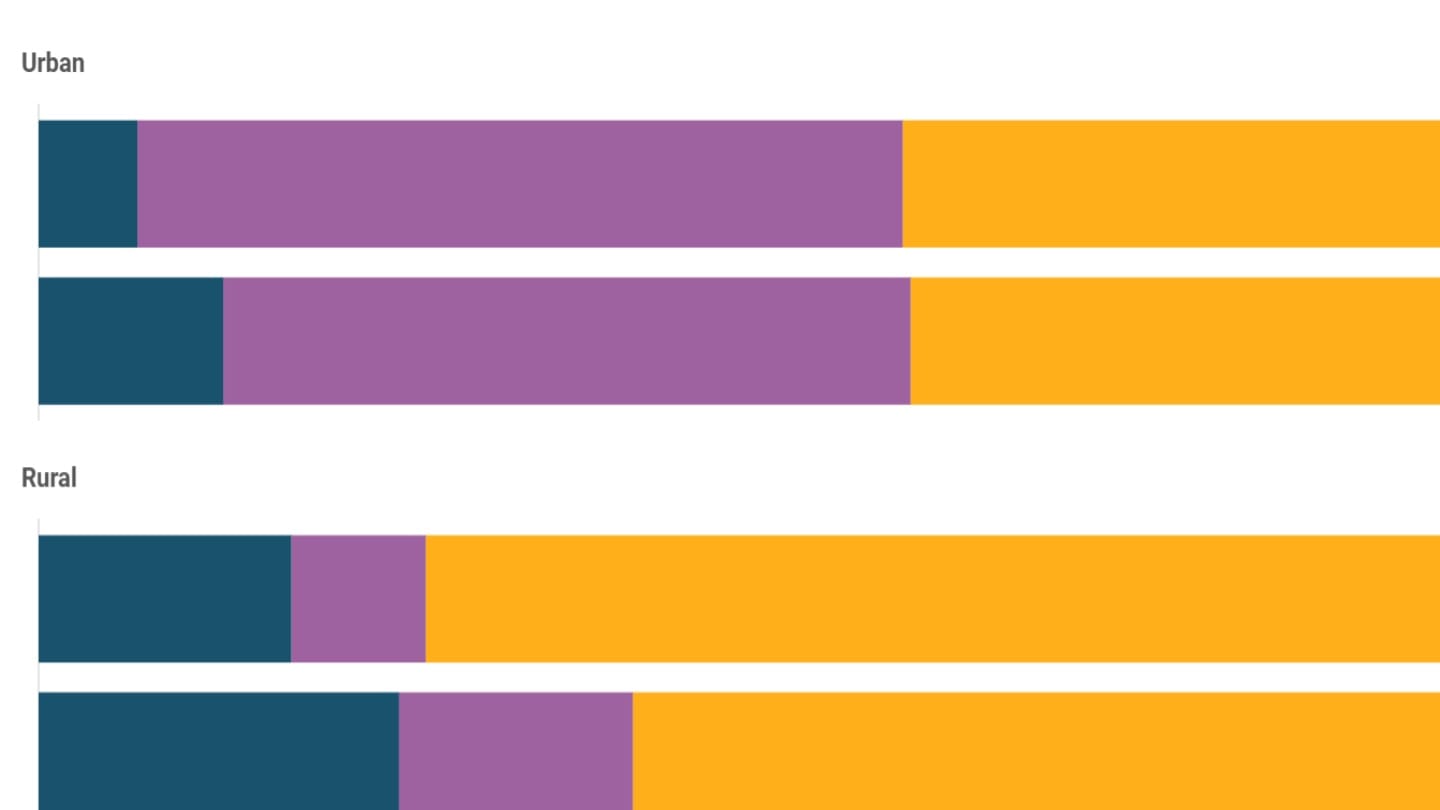

Labour force participation rates among men in India have always been roughly double those of women. Over time, however, labour force participation rates for both rural and urban men have fallen slightly.

Among women, labour force participation has always been higher among rural women. The LFPR for rural women fell sharply from 2005 onwards, but has recovered in the last five years. The labour force participation rate for urban women rose more modestly in comparison.

What takes men and women in and out of the workforce?

Most Indian men report that they are in the labour force.

When some men began to move out of the Indian labour force from the 1980s onwards, it was for education: male LFPR fell gradually from the 1980s with growing enrolment in education.[3]

Most adult Indian women, on the other hand, report that their main activity is "engaged in domestic duties" - housework and carework.[4]

When labour force participation rates for women rise, fewer women report that their main activity is housework, and when LFPR drops, more report housework as their main activity. This is particularly true for the current rise in female LFPR, where, alongside higher rates of labour force entry, enrolment in education has also risen, resulting in the lowest ever share of women who say that their main activity is housework.

What are the women who moved into the labour force doing?

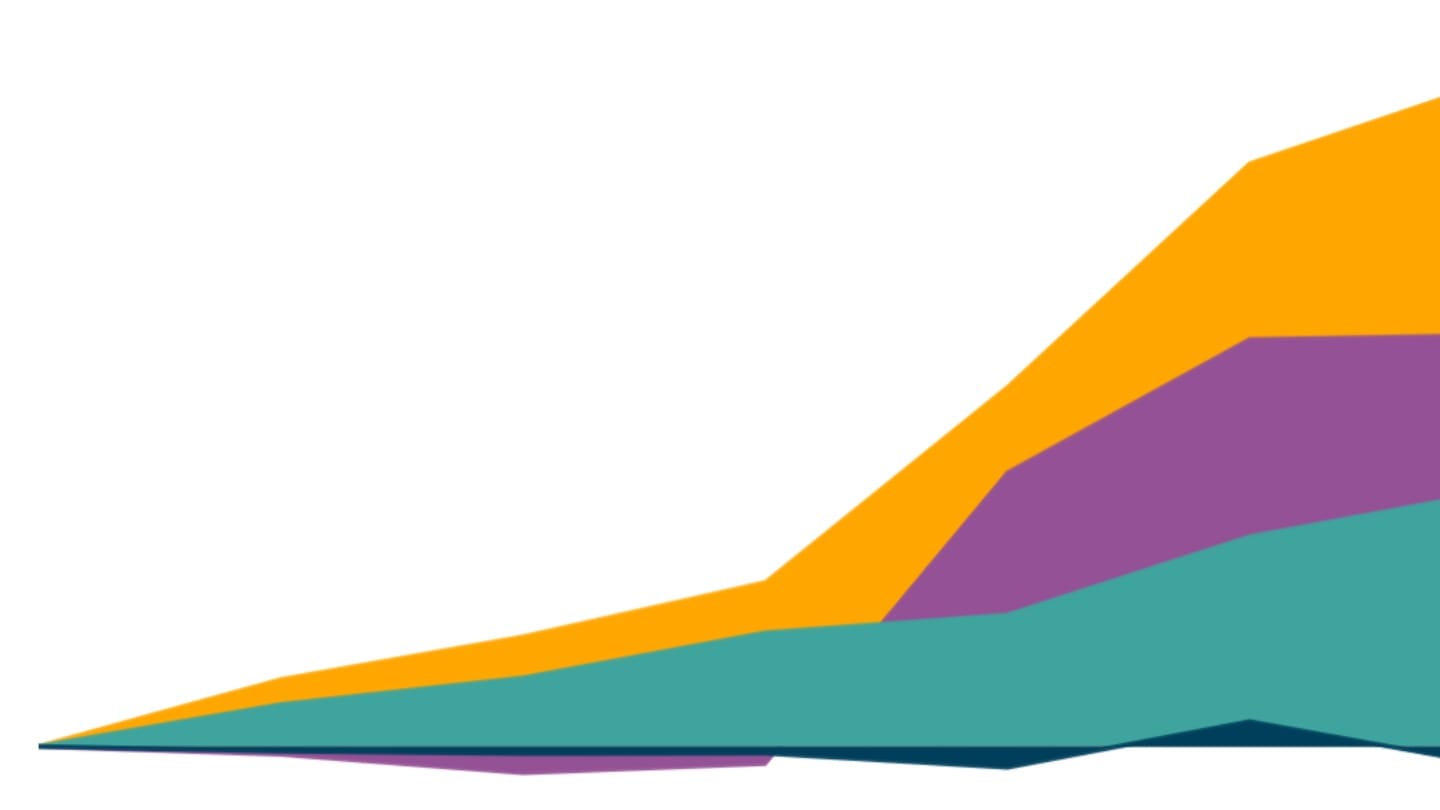

Sector of employment

In rural areas, most men and women are employed in agriculture. The decline in female labour force participation from the early 2000s onwards was heavily driven by the exit of a large number of rural women from agriculture. In recent years, 50 million rural women have returned to agriculture, bringing the level of female employment in agriculture back to its pre-2000s level.[5]

In urban areas, there has been a steady rise in employment in services for both women and men.

Nature of employment

In India's labour statistics, workers are classified depending on their working arrangements into four categories - salaried, casual workers, self-employed, and unpaid helpers.[6]

When female LFPR in rural India rose from the 1980s to the 2000s, the majority of newly added women in the workforce were unpaid helpers in household enterprises - typically women working on family farms or shops, but without being paid any wages. Unpaid helpers went from being a third of rural women workers in 1983 to nearly half in 2005.

The recent increase in female LFPR, meanwhile, has seen an increase in the share of self-employment among women in both rural and urban areas, meaning that this is work for which the woman is earning her own wage.

Long-term and short-term work

Most Indian workers are only principal workers, meaning that they work on one activity for most of the year, and this category has steadily grown for both men and women. However the recent rise in workers among both men and women in rural areas has primarily been in subsidiary work. Among rural women in particular, a large part of the recent increase has been in subsidiary work.

In urban areas, on the other hand, the increase for both men and women has primarily been in principal workers.

[1] Housework is also work, but is counted differently in labour statistics. See our explainer here.

[2] The Periodic Labour Force Survey records the activities of household members in two ways: Usual Status and Current Weekly Status. Data For India uses the Usual Status approach.

[3] Post-pandemic, there has been a small increase in male labour force participation.

[4] Labour surveys ask respondents what activity they spent most of their time on in the 365 days preceding the survey (principal activity), and enumerators then encode these responses as "worked as salaried employee", "did not work but was seeking and/or available for work", "attended educational institution", etc. They also ask about the economic activities the respondents were engaged in for shorter periods of time (subsidiary activity).

[5] Labour surveys help estimate relative shares and ratios, but are generally not used to generate estimates in absolute numbers. To estimate the absolute number of workers by sector, we used a combination of two estimates: workforce distribution from the national sample surveys (NSS) and the absolute population estimates from the single-year population data interpolated from Census data (actual data up to 2011, and projections from 2012 onwards).

[6] See this Data For India piece on employment for more explanation.