Do growth standards for Indian children measure up?

Global growth standards used to define the levels of child stunting in India have been contentious. While a substantial body of research shows that the standards are not inaccurate, more context-specific growth references could also be useful

Child stunting figures in India have been widely debated. One reason for this concern is that India's stunting rates are very high, comparable to those in much poorer Sub-Saharan African countries, and have declined slowly despite economic growth. This puzzling trend, sometimes called the "Indian enigma", has sparked decades of debate as experts try to understand and explain it. Much of the debate centres around concerns about applying global growth standards to the Indian context.

WHO Global Growth Standards

Metrics on child nutrition, such as stunting, are calculated by comparing a child's growth to standard growth trajectories derived from an international sample of healthy, breastfed infants and young children raised in environments that do not restrict growth.[1]

The current growth trajectories are based on data from the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study (MGRS), a cohort study conducted between 1997 and 2003. The MGRS collected primary growth data from 8,440 healthy, breastfed children across six culturally and geographically diverse countries: Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman, and the United States.[2]

Based on the data of the reference population, WHO set out the child growth standards that chart the expected growth trajectories from birth to age five. These include the median length/height and median weight for boys and girls at different ages (0 to 60 months), along with corresponding z-scores.

These z-scores indicate how far a child's anthropometric measurement deviates from the reference population's average, expressed in standard deviation (SD) units. For example, if a child's height is one standard deviation above or below the average, their z-score is 1 or -1, respectively. A height two standard deviations from the average gives a z-score of 2 (or -2), and so on.

Stunting is measured based on a child's height relative to their age. A child whose height-for-age z-score (HAZ) falls below minus two standard deviations (-2 SD) from the median of the reference population is considered stunted.[3]

In India, the WHO study focused on 58 relatively affluent neighbourhoods in South Delhi. The children selected had to meet strict criteria like being breastfed, living in smoke-free homes, receiving timely medical care, and access to clean water and sanitation. The goal was to measure the healthiest height and weight for each age when the common barriers to healthy growth are removed.

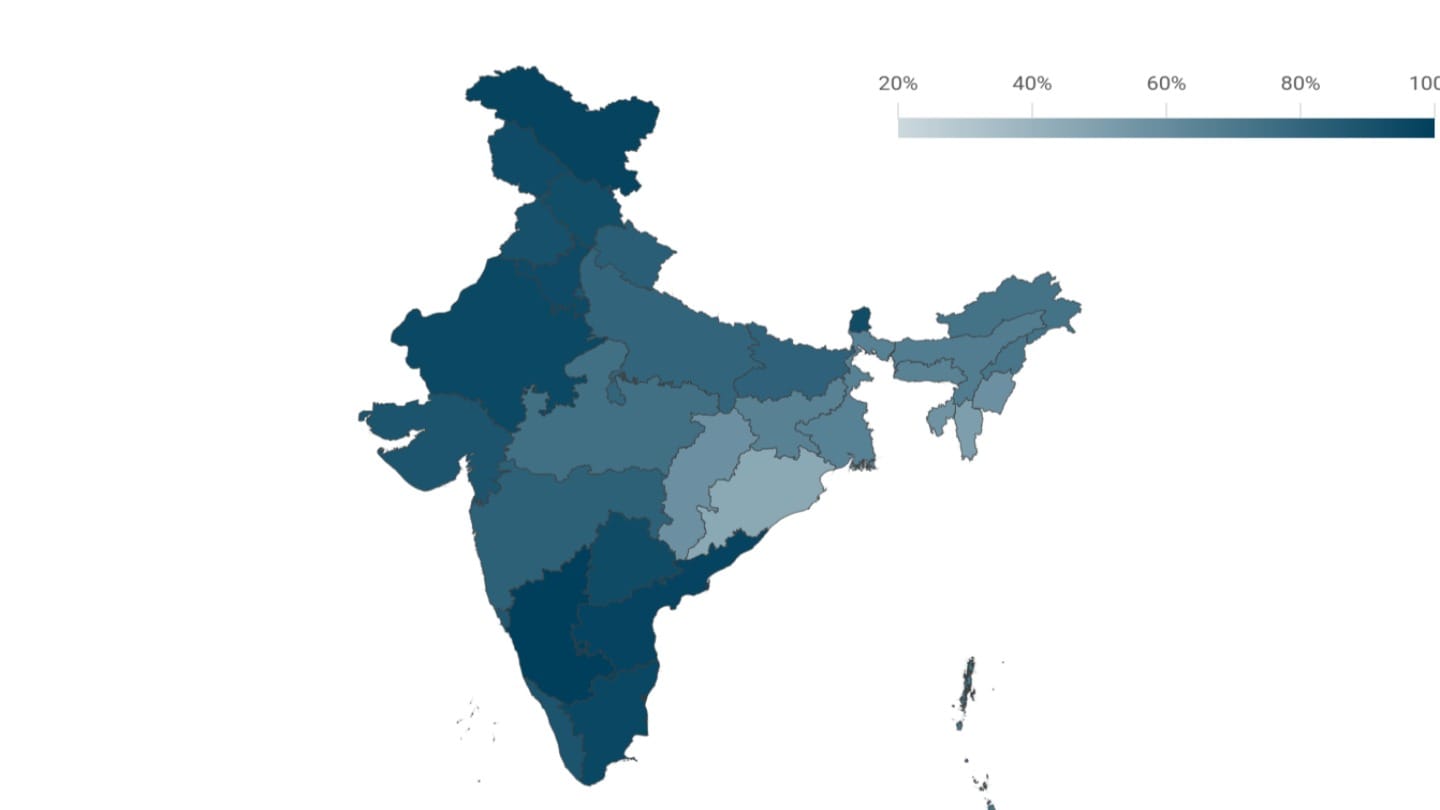

Since 2008, India has used these standards to track child growth in national surveys like the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) and the Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (CNNS). These standards are also used in programmes like the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) scheme for monitoring malnutrition.

Debate in India

However, not everyone agrees with using global growth standards for the Indian context. One line of objection stems from the argument that Indians are genetically shorter, making it unrealistic to expect children across all regions, races and cultures to reach the same height.[4] If this were the case, then global standards would be overstating India's stunting problem.

The WHO standards do not, however, expect every child to be of the same height, but define what they consider a healthy range. For example, the average height defined by the WHO for a three-year-old boy is 96 cm (3'2''). But a child is still considered healthy if he's anywhere above 89 cm (2'11''). This range covers 97% of children in the MGRS surveyed population.

Further, experts in favour of the WHO standards argue that the difference in height due to genetic potential is limited. One analysis of the data from all six countries found that the location was only responsible for a small fraction (3%) of height variation, while the vast majority was on account of differences between individual children. Even if one country's data was removed, the growth curves barely changed.[5]

This means children everywhere are more alike than different when given the right conditions.

Moreover, India is not genetically isolated. While Indians are genetically diverse, studies show there is significant genetic overlap between Indians and people from other parts of the world including Europe and Africa.[6] The available genomics data does not show that Indians have a unique genetic make-up, so the widespread stunting remains unexplained.

Genetics vs environment

Several studies have highlighted the fact that differences between rates of stunting between different populations that would seem to be explained by genetic differences can actually be attributed to differences in environment.

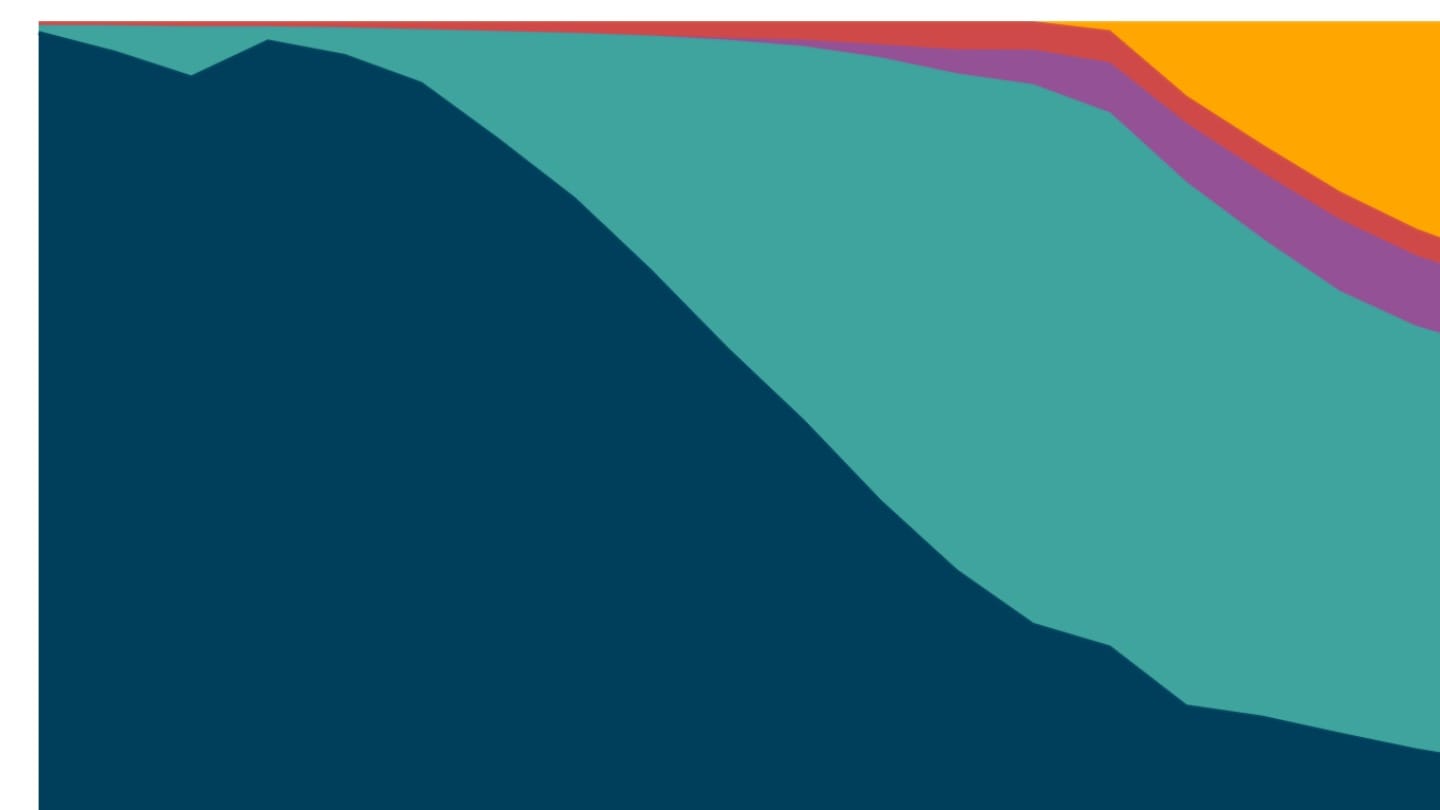

A study by Seema Jayachandran and Rohini Pande in 2013 found striking differences in child height within families.[7] India's height disadvantage shows up starting with the second-born child and gets worse with each additional birth. This suggests that it's not genetics, but how resources like food, care and attention are distributed among siblings that may be holding some children back. Using data from the DHS in India and Sub-Saharan Africa, they found that Indian firstborn children were actually taller than their African counterparts, further reinforcing how early life conditions and care can make a difference.

Evidence also comes from the heights of Indian immigrants to developed countries. A study in 2017 assessed the heights of Indian-origin children raised in England from Health Survey of England (HSE), along with NFHS data and found that children aged two to four, were not just taller than children in India, but were just as tall as White British children.[8] This wasn't because taller Indian parents moved to England; even after accounting for the height of the parents, children raised in England were about 6% taller than those raised in India.

Another notable study by Arabinda Ghosh and others in 2014 strengthens this argument, by finding that children in Bangladesh, although genetically similar to children from West Bengal, are significantly taller, on average, even when they come from similar socio-economic backgrounds.[9] This points to deeper issues in the Indian environment, not genetics.

Why is stunting in India worse than in similar countries?

If genetics isn't the reason, why does India, despite its growing economy, still have stunting rates as high as some of the world's poorest countries?

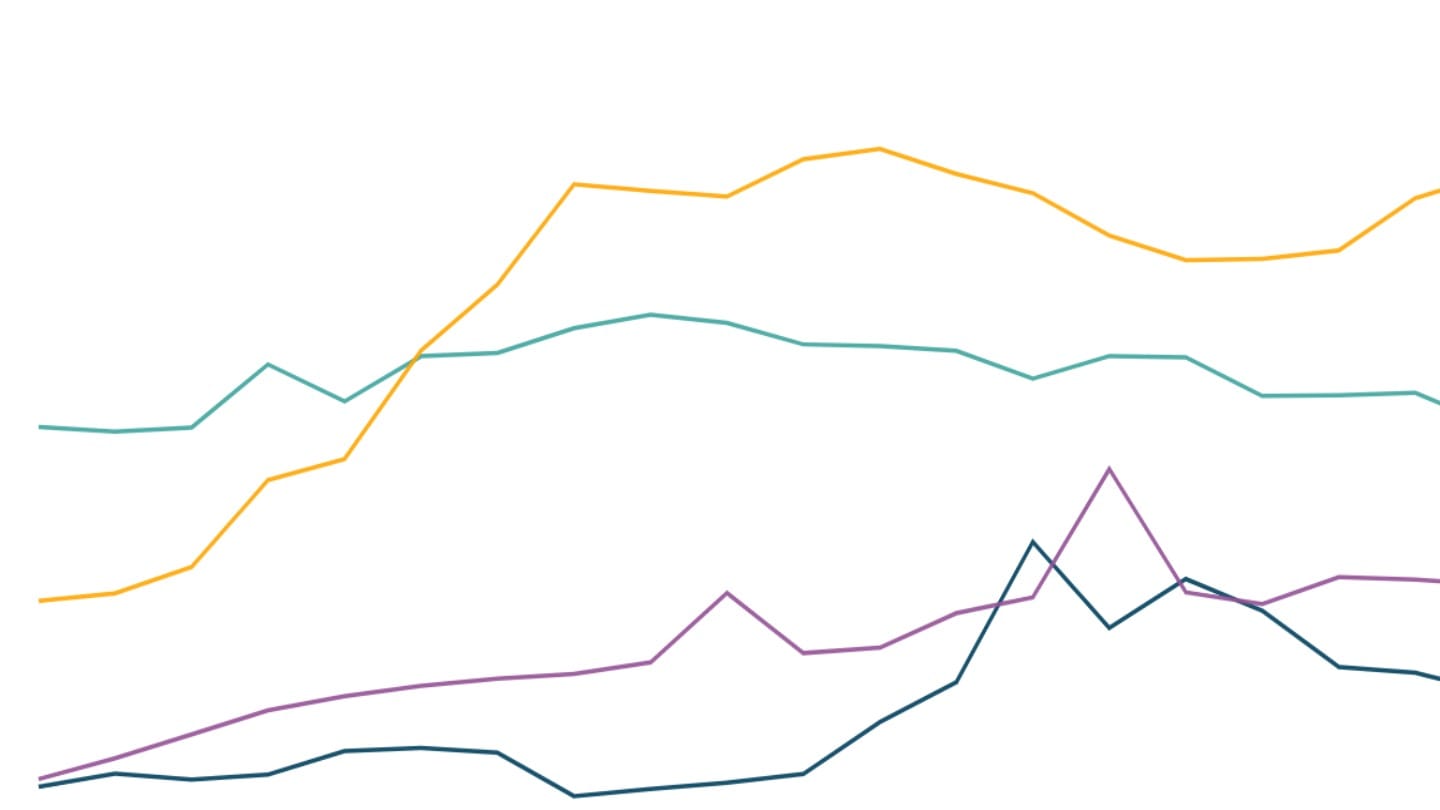

One important reason is the slow pace of generational catch-up. A child's height isn't only shaped by their own nutrition - it's also influenced by their mother's height.[10] Indian adults are short in stature, and Indian women are among the shortest in the world.[11]

Besides maternal height, other aspects of a mother's health are also crucial, as stunting largely occurs during the first 1,000 days of a child's life, which includes the prenatal period. In 2015, over two in five pregnant women were underweight and gained little weight during their pregnancies, which could in part explain stunting among their children.[12] A study of pregnant women in villages in Maharashtra found that they were poorly nourished, raising the risk of low birth weights and stunting among their children.[13]

The children of Indian women who face further disadvantages - including belonging to Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes[14] or being the younger daughters-in-law of joint families[15] - are even shorter.

Another major factor is exposure to open defecation, which continues to affect child health on a large scale. Frequent exposure to poor sanitation leads to repeated infections, especially in early childhood, which prevents proper nutrient absorption and affects growth. Despite having high rates of mortality from serious illnesses like HIV and malaria, which India does not, Sub-Saharan Africa has low rates of open defecation. Studies have shown that differences in rate of open defecation explain a significant share of the gap in child height between India and Sub-Saharan Africa.[16]

Growth standards and growth references

One key distinction matters when considering whether the stunting indicator fairly captures the nutritional and other deficits of Indian children - the difference between a growth standard and a growth reference. A growth standard, such as the WHO global standard used to measure stunting, shows how children should grow in ideal conditions. A growth reference, on the other hand, shows how children are growing in a specific population at a specific time.

What could also be useful, then, to understand the current nutritional deficits of Indian children and how they are changing are growth references that are more relevant for India, and for present times.[17]

Some countries use a mix of the WHO standards and national references.[18] The USA uses WHO standards for children under two, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) references thereafter for continuity since the CDC tracks children until the age of 19, and WHO charts only go up to age five. For ages two to five, both CDC and WHO charts are based on very similar methods. The UK and Indonesia also use WHO charts nationally, with only minor adaptations for local context.

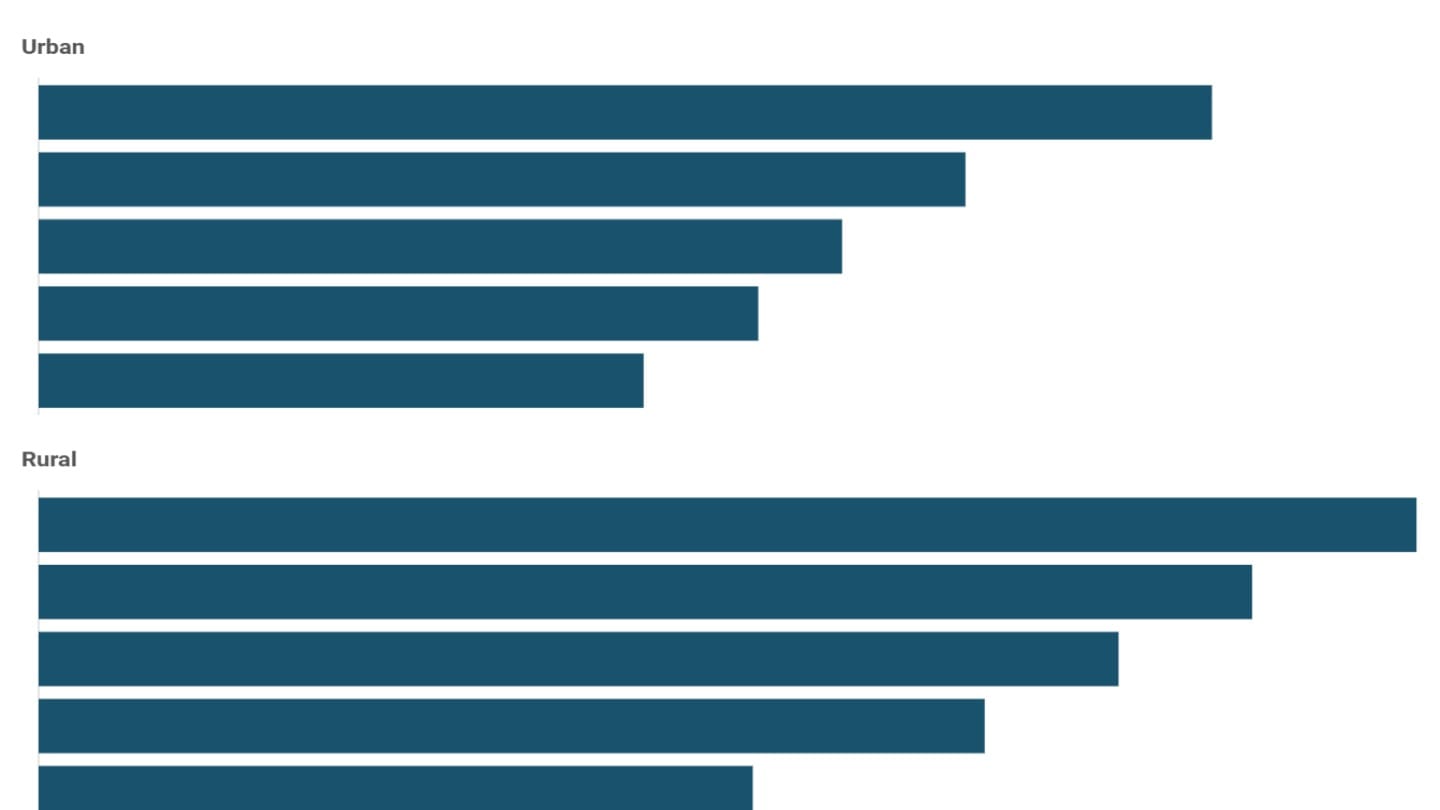

One proposed India-specific growth chart is based on a sample of children from urban middle- and upper-middle-class households across the country using data from the fifth round of NFHS conducted in 2019-21.[19] Based on this growth chart, the stunting rate in India would drop to 24%, compared to 35% based on WHO standards. Another proposal suggests adjusting WHO-based estimates by factoring in maternal height, which would control for the inter-generational component.[20] The prevalence of maternal-standardised stunting was 25% using NFHS-4 data as reference, compared to 38% based on WHO standards for the same year.[21]

The WHO standards are prescriptive, not descriptive. Their value is in being able to show what's ultimately possible for every child given the ideal health, social and environmental conditions for all people. This can mean that such aspirational standards might have limited immediate utility, especially when we know that meeting them can take generations.[22] For the purposes of shorter-term monitoring and policy-framing, more tailored growth standards could provide a roadmap.[23] However, such national standards will make it difficult to compare the pace of change in stunting among Indian children with other countries.

[1] WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age (2007), WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group, Acta Paediatrica.

[2] WHO child growth standards (2006), World Health Organization.

[3] Suppose a 36-month-old boy is measured to be 88 cm tall. According to the WHO growth standards, the expected median height for boys at this age is 96.1 cm, and the cut-off for stunting (height-for-age z-score) at -2 SD is 88.7 cm. Since the child's height (88 cm) is below this threshold, he is classified as stunted.

[4] Does India Really Suffer from Worse Child Malnutrition Than Sub-Saharan Africa? (2013), Arvind Panagariya, Economic and Political Weekly.

[5] Methodologically Deficient, Ignorant of Prior Research (2013), Gargi Wable, Economic and Political Weekly.

[6] Methodologically Deficient, Ignorant of Prior Research (2013), Gargi Wable, Economic and Political Weekly.

[7] Choice Not Genes - Probable Cause for the India-Africa Child Height Gap (2013), Seema Jayachandran, Rohini Pande, Economic and Political Weekly.

[8] Leaving stunting behind: Evidence from ethnic Indians in England (2017), Caterina Alacevich, Alessandro Tarozzi, Ideas for India.

[9] Are Children in West Bengal Shorter Than Children in Bangladesh? (2014), Arabinda Ghosh, Aashish Gupta, Dean Spears, Economic and Political Weekly.

[10] Maternal Height-standardized Prevalence of Stunting in 67 Low- and Middle-income Countries (2022), Omar Karlsson et al, Journal of Epidemiology.

[11] Height and body-mass index trajectories of school-aged children and adolescents from 1985 to 2019 in 200 countries and territories (2020), NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC).

[12] Prepregnancy body mass and weight gain during pregnancy in India and sub-Saharan Africa (2015), Diane Coffey, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

[13] Compromised maternal nutritional status in early pregnancy and its relation to the birth size in young rural Indian mothers (2021), Devaki Gokhale & Shobha Rao, BMC Nutrition.

[14] The Missing Piece of the Puzzle: Caste Discrimination and Stunting (2021), Ashwini Deshpande, Rajesh Ramachandran, Centre for Economic Data and Analysis (CEDA), Ashoka University.

[15] Women's status and children's height in India: Evidence from joint rural households (2014), Diane Coffey, Reetika Khera, and Dean Spears.

[16] Exposure to open defecation can account for the Indian enigma of child height (2020), Dean Spears, Journal of Development Economics.

[17] A working paper published by the Prime Minister's Economic Advisory Council also pushed for adopting a national standard, arguing that other countries like the USA, UK and Indonesia have done the same. (Reversing the Gaze (2023), Sanjeev Sanyal et al., EAC-PM Working Paper Series).

[18] Review of WHO Growth Standards and their Relevance for India (2023), Vandana Prasad, Dipa Sinha.

[19] Should India adopt a country-specific growth reference to measure undernutrition among its children? (2023), S.V. Subramanian et al., The Lancet Regional Health (Southeast Asia).

[20] Revisiting the stunting metric for monitoring and evaluating nutrition policies (2022), S. V. Subramanian, Omar Karlsson, Rockli Kim, The Lancet.

[21] Review of WHO Growth Standards and their Relevance for India (2023), Vandana Prasad, Dipa Sinha.

[22] Should a single growth standard be used to judge the nutritional status of children under age 5 years globally? No (2024), Harshpal Singh Sachdev, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

[23] Should India adopt a country-specific growth reference to measure undernutrition among its children? (2023), S.V. Subramanian, The Lancet Regional Health (Southeast Asia).