Malaria in India

India has made large strides in reducing the annual incidence of malaria and deaths from the disease. However, malaria remains a major public health challenge, particularly in central and eastern states, and among young children.

India had nearly eradicated malaria in the 1960s, but it came back strongly by the mid-1970s.[1] India aims to reach zero indigenous malaria cases by 2027 and achieve full elimination by 2030.[2] More than a hundred countries have already eliminated the disease, including South Asian nations like Sri Lanka and the Maldives.[3]

Even though malaria remains a key contributor to death from infectious diseases in India, particularly among younger children, mortality from malaria has reduced substantially. However challenges remain, one of them being the lack of reliable data.

Malaria in India and the world

Malaria is a potentially life-threatening disease caused by plasmodium parasites, transmitted through the bites of infected female anopheles mosquitoes. Stagnant water serves as a breeding ground for mosquitoes, contributing to its spread. As a result, the highest incidence of cases in most parts of the country is during the rainy season from July to November.[4]

Severe malaria in children can lead to complications such as severe anemia, respiratory distress, or cerebral malaria. In adults, it can result in multi-organ failure.[5] Among pregnant women, malaria can impact maternal health and pregnancy outcomes.[6]

Data on the incidence of malaria - new cases reported every year - can come from either direct surveillance and reporting, or from a combination of direct numbers and modelling. Directly reported data on the incidence of malaria from the Indian government[7] remains limited;[8] as a result we use modelled estimates from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation[9] for disease incidence data for this piece. (For a detailed discussion of malaria data, see this piece in our Measurement section.)

In 2020, an estimated 3.2 million new malaria cases were reported in India, down from an estimated 33 million in 1990.[10]

The decline in India is far sharper than it was in the rest of the world. In 1990, the number of new cases of malaria every year in India closely mirrored the global malaria incidence rate of around 4,000 new cases every year for every 100,000 people. By 2020, the global incidence rate decreased to 3,000 new cases for every 100,000 people, while India's rate fell sharply to less than 230 per 100,000 people.

Mortality from malaria

To understand mortality (deaths) from malaria, we use data from the Sample Registration System (SRS) Cause of Death Survey. This is a large-scale nationally representative sample survey conducted by India's Registrar General. The SRS uses verbal autopsies to assign causes of death reported in sample households, and is our preferred source over modelled estimates from IHME. (For a full discussion on sources of data on mortality and their merits, see this piece in our Measurement section.)

There has also been a sharp decline in mortality (deaths) from malaria in India. In 2005, malaria caused an estimated 209,000 deaths in the country, but by 2022 this number was down to around 9,400.[11]

Globally, the absolute number of deaths from malaria has remained relatively steady since the 1990s, but India has made significant progress in reducing its share of these deaths. While the global malaria death rate declined modestly from 14 deaths annually attributed to malaria for every 100,000 people in 1990 to 9 per 100,000 people in 2020, India achieved a far more dramatic drop, from 10 to just 1 death per 100,000 people during the same period.

Even with this progress, malaria is still responsible for one out of every 1,000 deaths in India.[12]

Impact on different age groups

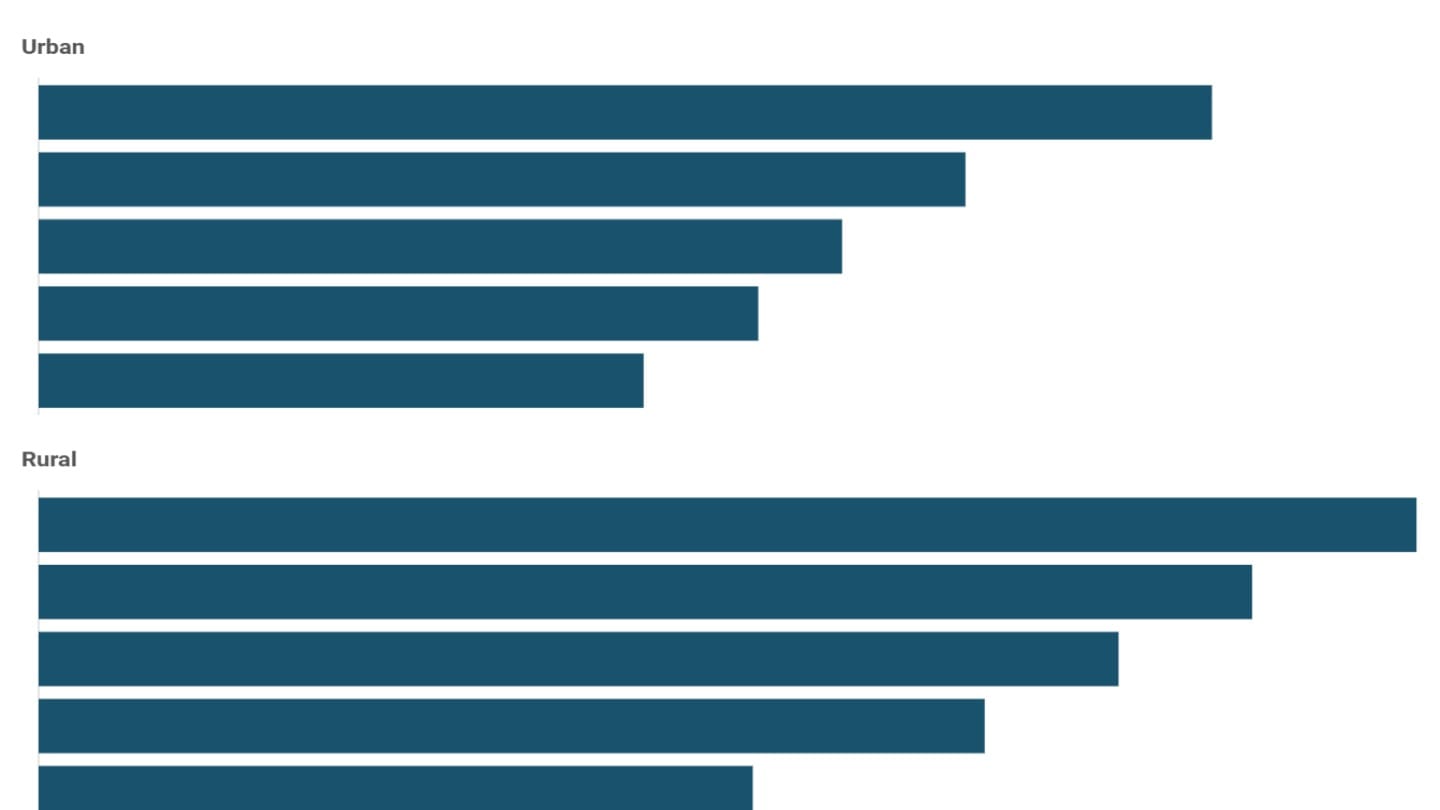

Malaria impacts people from different age groups differently. On account of their high exposure, those in the 25-40 age group are most likely to contract malaria. Incidence rates are highest in this age group, with about 300 new cases reported for every 100,000 people in this age group in 2020.

While malaria-related deaths are most prevalent among children aged 5-14, there has been a significant decline since 2005, when nearly one in ten deaths in this age group were attributed to the disease.

State-wise patterns

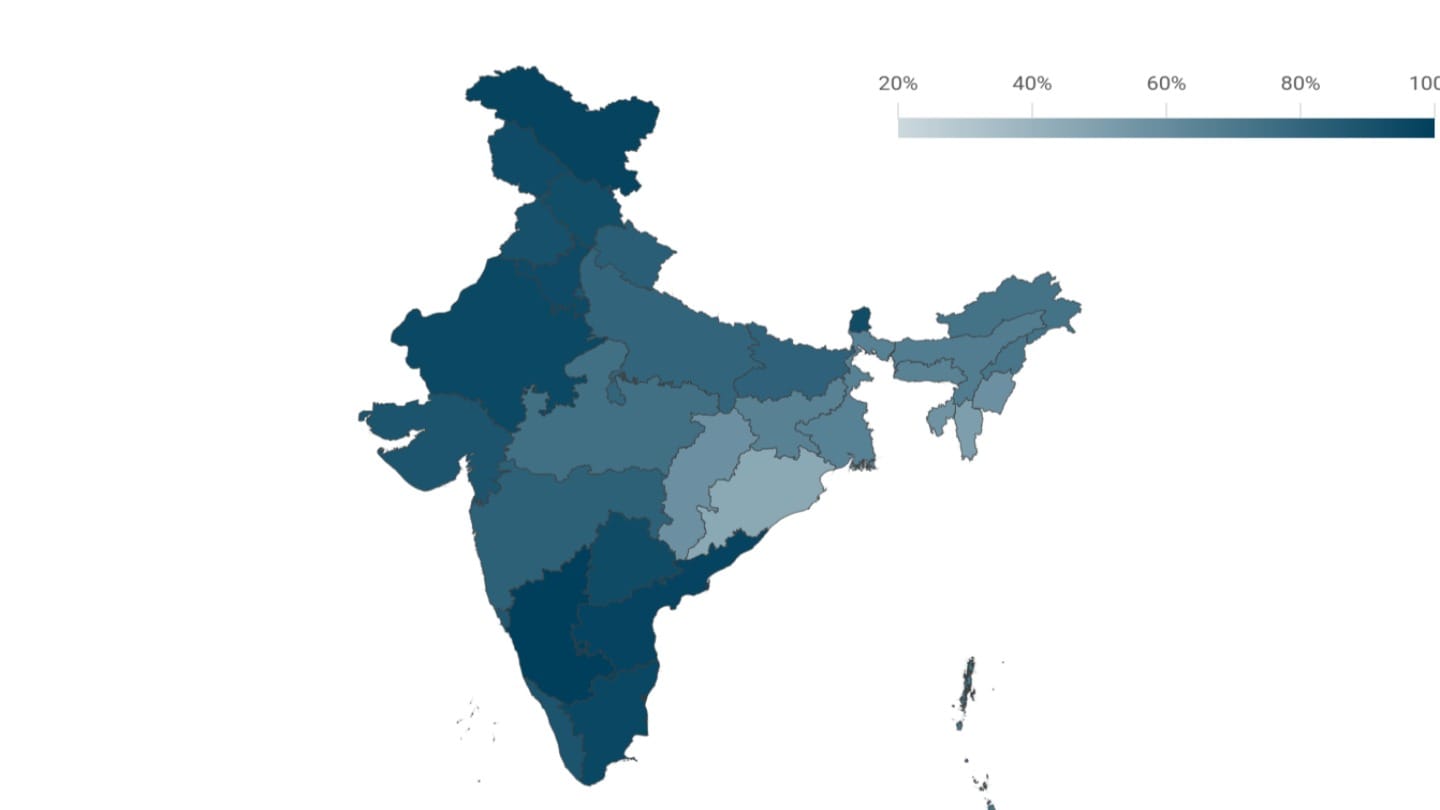

India has made substantial progress in reducing malaria cases and deaths, but the pace of improvement has varied across states, and some areas have reported recent surges potentially on account of drug resistance.[13] For both incidence and deaths at the state-level, we use data from IHME[14], as no other state-level estimates exist. (See this piece in our Measurement section for more details.)

Malaria is not evenly distributed across India, with 80% of the disease burden concentrated among 20% of the population classified as "high risk".[15] Chhattisgarh, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat alone contribute to nearly half of India's malaria cases. Incidence rates in 2020 were highest in Mizoram and Chhattisgarh, where 1 in 50 people contracted the disease, followed by Jharkhand with 1 in 100 people affected.

Regions with high tribal populations are disproportionately affected, contributing to 32% of malaria cases and 42% of malaria-related deaths, despite accounting for just 6.6% of India's population.[16] Malaria in these areas is driven by unique challenges, including difficult-to-reach forested and hilly terrains, climatic conditions favouring mosquito and parasite proliferation, and limited healthcare access.[17]

Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha together account for over half of all malaria deaths in India.[18] In Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, about one in 100 deaths in 2020 were attributed to malaria during the same period.

The future of malaria in India

Malaria is both a preventable and a treatable disease. Malaria prevention involves strategies aimed at reducing mosquito exposure. Treatment focuses on prompt diagnosis and effective medication.

Some African nations have begun to use WHO-recommended vaccines for children. However, a significant proportion of malaria cases in India are caused by p. vivax, which is not targeted by the RTS,S/AS01 vaccine, the first malaria vaccine approved by the WHO in 2021.[19] An anti-malarial vaccine being developed by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) also targets p. falciparum only.[20]

The R21/Matrix-M vaccine, approved by WHO in 2023, is effective against both p. vivax and p. falciparum.[21] India has yet to adopt these vaccines on account of its relatively low malaria transmission rates and mortality figures compared to high-burden regions in Africa.

[1] Early efforts, including widespread insecticide spraying and active surveillance, led to a decline in malaria cases, nearing eradication in the 1960s with fewer than 100,000 new cases annually. However, by the mid-1970s, cases surged to about 6.4 million due to increasing resistance to insecticides like DDT and drugs such as chloroquine, compounded by operational and logistical challenges. Source: Burden of Malaria in India: Retrospective and Prospective View, American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene

[2] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare

[4] National Strategic Plan Malaria 2023-27, National Centre for Vector Borne Diseases Control

[6] Prevalence of Pregnancy Associated Malaria in India, Frontiers in Global Women's Health

[7] The National Centre for Vector Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC), under the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW) conducts both passive surveillance (cases reported at health facilities) and active surveillance (targeted blood sampling in high-risk areas)

[8] The incidence data from NCVBDC is far lower than other estimates, and is an under-estimation by the government's own admissionFor example, in 2019, NCVBDC reported 3.4 lakh malaria cases, whereas modelled estimates from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) suggests close to 5.5 million cases - about 16x higher.

[9] The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation's Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study combines data from diverse sources, including government registries, surveys like DHS, and entomological studies. Using statistical models and covariates like climate and population density, it provides incidence estimates.

[10] The most recent data available from IHME is for 2021; however, as IHME uses modeling to estimate mortality, the global impact of COVID-19 may have affected these calculations. Therefore, for accuracy and consistency, this piece references 2020 figures instead which have more precise confidence interval ranges.

[11] Sample Registration System Cause of Death Report. The SRS provides only the share (percentage) of deaths by gender and age group that can be attributed to a particular cause. We apply these percentages to the estimated total annual deaths to generate estimates of the absolute numbers of deaths from malaria. For years after 2011, total deaths are calculated by applying mortality rates from the SRS annual statistical report to the Census 2011 population projections, while for 2005 they are derived through geometric interpolation between the 2001 and 2011 census data.

[12] Sample Registration System Cause of Death Report.

[14] Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation's Global Burden of Disease (GBD)

[15] High-risk malaria areas are determined based on the Annual Parasite Incidence (API). API is the number of confirmed malaria cases detected through active and passive surveillance per 1,000 population in a given area annually. API is determined by collecting and examining blood samples for malaria parasites from individuals reporting fever, either proactively (active) or upon seeking treatment (passive). Areas are classified as high-risk if the API exceeds a certain threshold, typically API > 1. Source: National Framework for Malaria Elimination

[16] What India can learn from globally successful malaria elimination programmes, BMJ Global Health Journal

[17] Burden of tuberculosis & malaria among tribal populations & implications for disease elimination in India, Indian Journal of Medical Research

[18] Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation's Global Burden of Disease (GBD). The most recent data available from IHME is for 2021; however, as IHME uses modeling to estimate mortality, the global impact of COVID-19 may have affected these calculations. Therefore, for accuracy and consistency, this piece references 2020 figures instead which have more precise confidence interval ranges.

[19] World Health Organization

[20] Invitation for Expression of Interest (EoI), ICMR

[21] Should India be considering deployment of the first malaria vaccine RTS,S/AS01?, BMJ Global Health Journal