How India measures literacy

Literacy rates are rising fast in India. But how literacy is defined matters, as does the manner in which surveys on literacy are conducted, resulting in some illiterate people being missed from official statistics.

India has made great strides in eliminating illiteracy. In this piece we examine how literacy and illiteracy are measured in India, and the implications of the choice of methodology and indicator.

The globally accepted United Nations definition of literacy is being able to read and write a simple sentence in any language with understanding, and Indian surveys also use this definition.[1]

Ever since their introduction in 1950, all rounds of the nationally representative household surveys from the National Statistics Office (NSO) have recorded the educational levels of the members of the surveyed households, including their literacy status.[2]

The National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) have also measured literacy over five surveys conducted since 1992.

Both surveys use different methodologies, which affect their findings.

NSO surveys

The National Sample Surveys conducted by the NSO survey a representative sample of Indian households. Enumerators collect data on the educational levels of all household members of a sample household as part of the background information.

In each sample household, the "informant" - usually the head of the household - answers the questions. The enumerator asks the informant about the highest completed level of education of every household member. If an informant reports that a household member has very limited education or is unable to communicate, the enumerator asks the informant if that person can read or write. The enumerator does not administer a test and must take a call herself - the instructions say that "persons who are not able to read and write a simple message with understanding in at least one language are to be considered illiterate", and the enumerator must satisfy herself of the correctness of the response.

One recent NSS survey takes a slightly different approach. The Comprehensive Annual Modular Survey (CAMS) conducted in 2022-2023, asks the informant about the enrolment status of household members, and asks about the reading/writing ability of only those members who were never enrolled in school. This survey too does not conduct a literacy test.

National Family Health Survey

The intent of the National Family Health Survey is to record health and demographic parameters in addition to a few household characteristics. As part of the background information of the respondents, the NFHS asks about literacy.

The NFHS asks women between the ages of 15 and 49, and men between the ages of 15 and 54 about their highest completed educational level. Those who were educated up to the primary level only are asked to read a simple sentence from a card carried by the enumerator.[3] Those who say they have a secondary or higher education are not administered a literacy test.

In earlier rounds, the NFHS simply asked the informant about the literacy levels of all household members, and did not conduct a test. This was similar to the NSO's system for measuring literacy.

What the data on literacy misses

The manner in which the NSS and NFHS ask the literacy question opens up the possibility that some illiterate people are being missed.

First there is the question of whether a survey without a literacy test can produce accurate data on literacy.

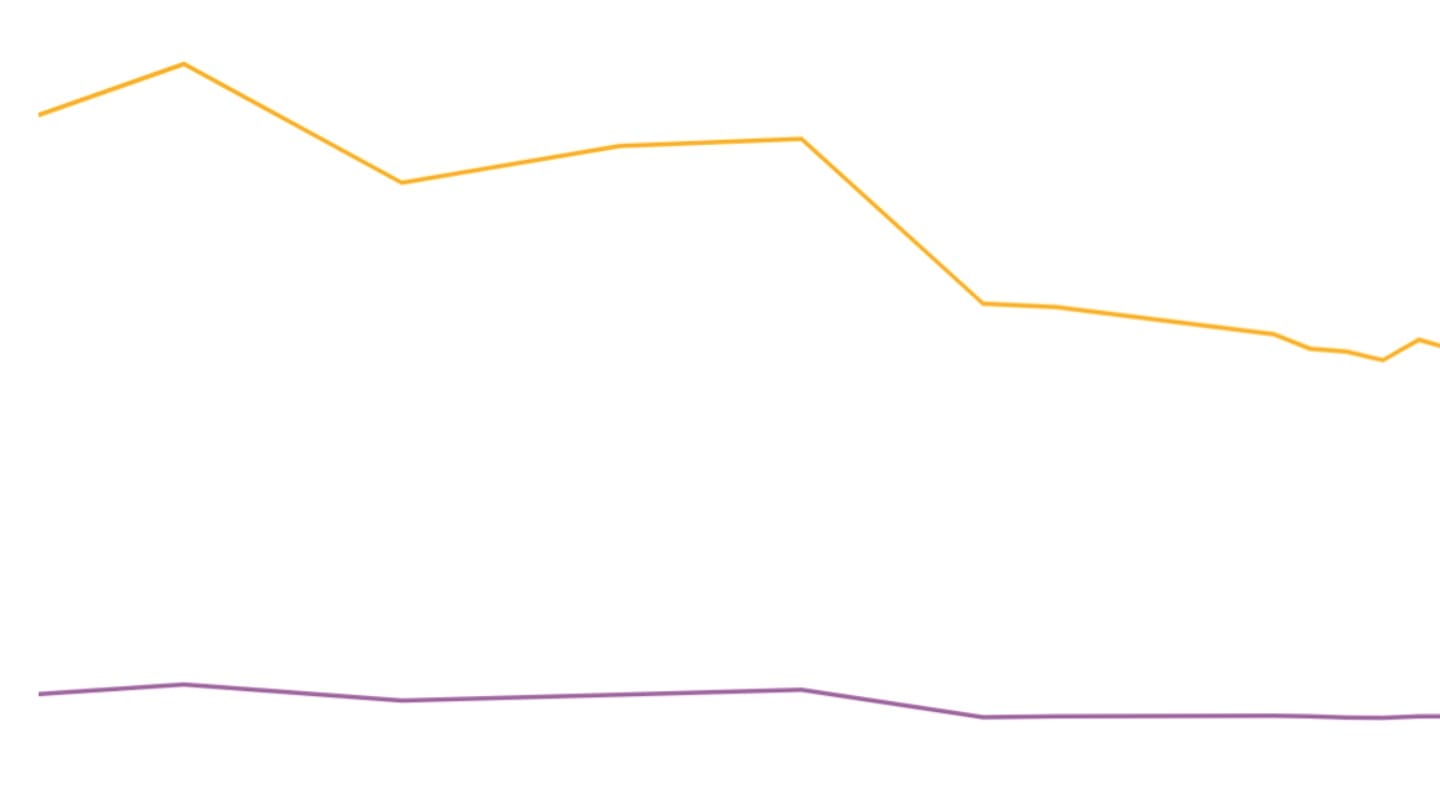

In the years when the NFHS did not conduct any literacy test and only asked the informant about the literacy levels of household members, it produced much higher estimates of literacy than in later years, when household members with only a primary education had to take a literacy test. In 2004-05, when the NFHS 3 recorded literacy using both the methods, it found the literacy rate to be 69% when demonstration was not required, and 63.4% when the respondent had to read the literacy test card.

Additionally, for years when the NFHS and NSO surveys were conducted in the same year or in years close to each other, the NFHS surveys that included a literacy test recorded lower levels of literacy than the NSO surveys.[4]

Second, there is the question of whether informants can correctly estimate the literacy levels of household members.

In 1991, India conducted a special one-off survey on literacy (Round 47). The survey asked a sample of people whether all household members were literate. The enumerators then tracked down people whom informants had reported as literate, but who had not studied past primary school.[5] More than 10% of such people when contacted individually reported that they were actually illiterate.[6]

Thirdly, not everyone who thinks they are literate may actually be literate. Enumerators in the 1991 NSO literacy survey then conducted literacy tests on the remaining 90%, who had an education below primary level but had reported themselves to be literate.[7]

They found that only 70% of them were able to do both reading and writing with comprehension, meaning that they really were literate.

Finally, there is the fact that all surveys assume that some people are literate and do not ask them the literacy question at all. Routine NSO surveys do not ask informants about the literacy levels of household members whom the informant has said are educated. The CAM survey does not ask informants about the literacy levels of people who were ever enrolled in school. The NFHS does not administer the literacy test on those with a secondary or higher education. All of them are assumed to be literate.

The reason this is problematic is because we now know that merely having gone to school is not an automatic guarantee of literacy.

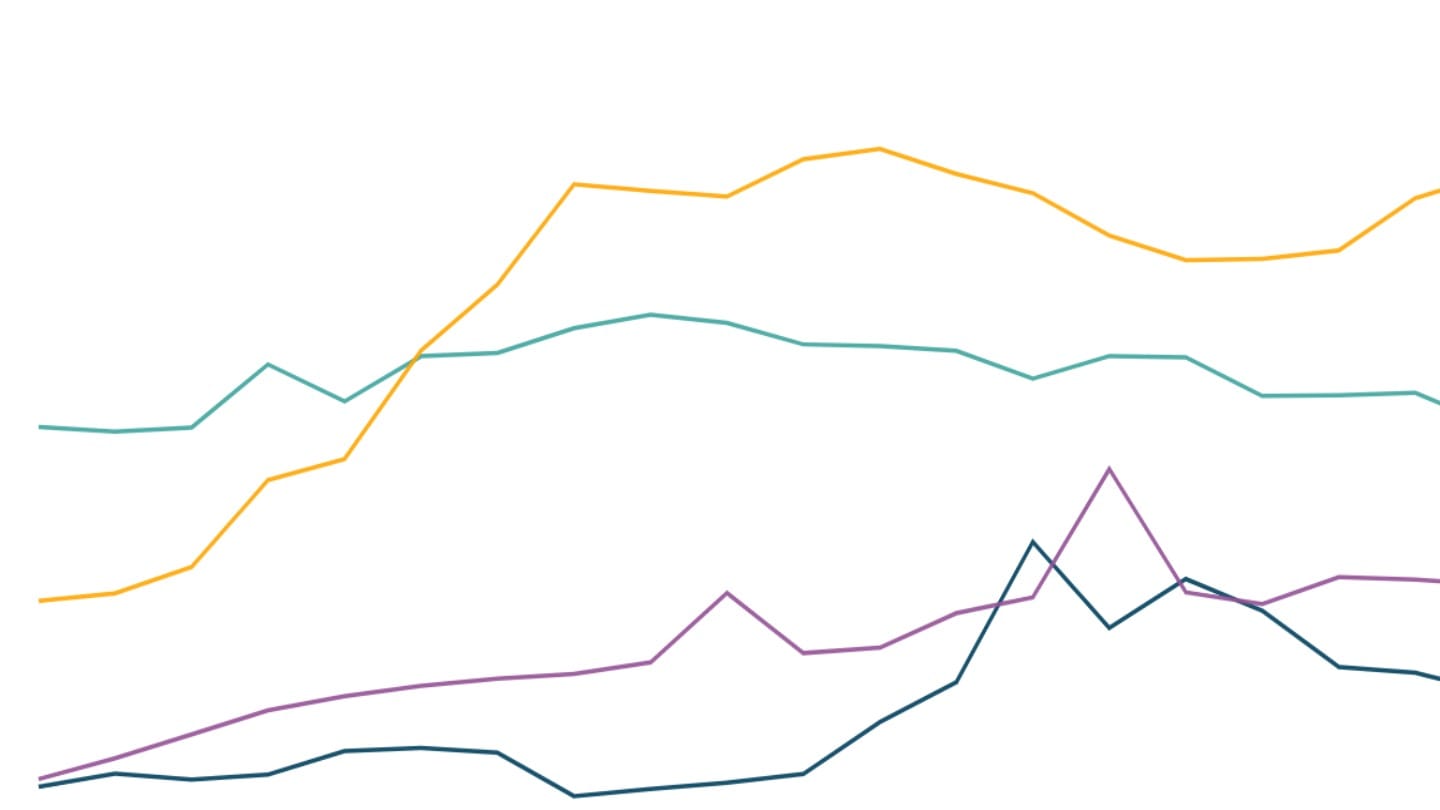

Pratham is a non-governmental organisation in India which began conducting the Annual Status of Education Reports (ASER) surveys in rural India in 2005. These nationally representative household surveys measure learning outcomes, functional literacy and numeracy skills among school-age children.

ASER asks children in Grade 8 from selected households to read a text.[8] In 2005, ASER estimated that 86% of children in Grade 8 were able to read a Grade 2-level text with some long sentences. In 2022, the proportion of children in Grade 8 who were able to read a Grade-2 level text fell to 70%. Moreover, 2.5% of children in Grade 8 could not even identify letters in their own language. It suggested a worsening of functional literacy among school children.[9]

This also has implications on the assumption of surveys that everyone who completed school is literate, and on the literacy rates that such surveys produce.

[1] The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) definition of literacy in 1958 was: A person is literate who can with understanding both read and write a short simple statement on his (her) everyday life. (b) A person is illiterate who cannot with understanding both read and write a short simple statement on his (her) everyday life.

The 1989 definition was: A person is "literate" who says he/she can both read and write (with understanding) a short simple statement on his/her everyday life in a language of his/her choice.

[2] The Indian Census also measures literacy. However India has not conducted a census since 2011. As a result, we do not use Census data in this piece.

[3] From the questionnaire: Each card should have four simple sentences appropriate to the country (e.g., "Parents love their children.", "Farming is hard work.", "The child is reading a book.", "Children work hard at school."). Cards should be prepared for every language in which respondents are likely to be literate.

[4] The NFHS records the responses as: Cannot read at all, Able to read only parts of sentence, or Able to read whole sentence. 60% women in the age group 15-49 were able to read the complete sentence in NFHS 5 (2019-2021), while 12% were able to read it partially. Among men between 15 and 54 years of age, 70% were able to read the whole sentence, while 13% were partially literate. We consider both those who could read parts of the sentence or the whole sentence as literate.

[5] Above 15 years of age.

[6] Although the sample size of the survey was about 300,000 individuals, the filters applied reduced the number of individuals tracked for the re-survey to 5,400.

[7] Enumerators on this survey carry text for individual respondents to read to demonstrate their reading ability. These passages are in 31 Indian languages. The enumerators also ask a few questions about the written matter in the passage to verify if the respondents have understood what they read.

[9] ASER 2022 national findings.