Mortality in India

Over the last 50 years, India has radically lowered the risk of dying young.

Over the last century, life in India has got safer - a child born in India can expect to live longer than her parents and grandparents did and the risk of dying young has declined steadily.

Mortality in India and the world

Around 9.5 million people die in India every year. This is the second largest number of annual deaths of any country in the world after China, but that's just a function of India being the world's most populous country. Accounting for population, India's Crude Death Rate - the number of deaths for every 1,000 people - is lower than the global average.

It's also falling over time.[1] While India has added over a billion people between 1950 and 2025, the number of annual deaths remained quite stable at between eight and ten million deaths every year over the same period. As a result, India's Crude Death Rate has fallen steadily.

Mortality in early childhood

The key driver of falling mortality in India has been the dramatic lowering of risks to the life of India's infants.

Wherever you live in the world, early childhood, especially infancy (the period before a child turns one) is a time of relatively high risk compared to later in life. Over half of all infant deaths in India take place within the baby's first week of life ("early neonatal mortality"), and three in four within the first month ("neonatal mortality"). The elevated risk of mortality for an Indian infant begins before they are born and is strongly linked to the mother's health.[2]

In the poorer regions of the world, infancy is a particularly dangerous time, when a combination of birth disadvantages as a result of maternal undernutrition and the high risk of contracting communicable diseases pose significant challenges. Over half a million infants died in India in 2025.

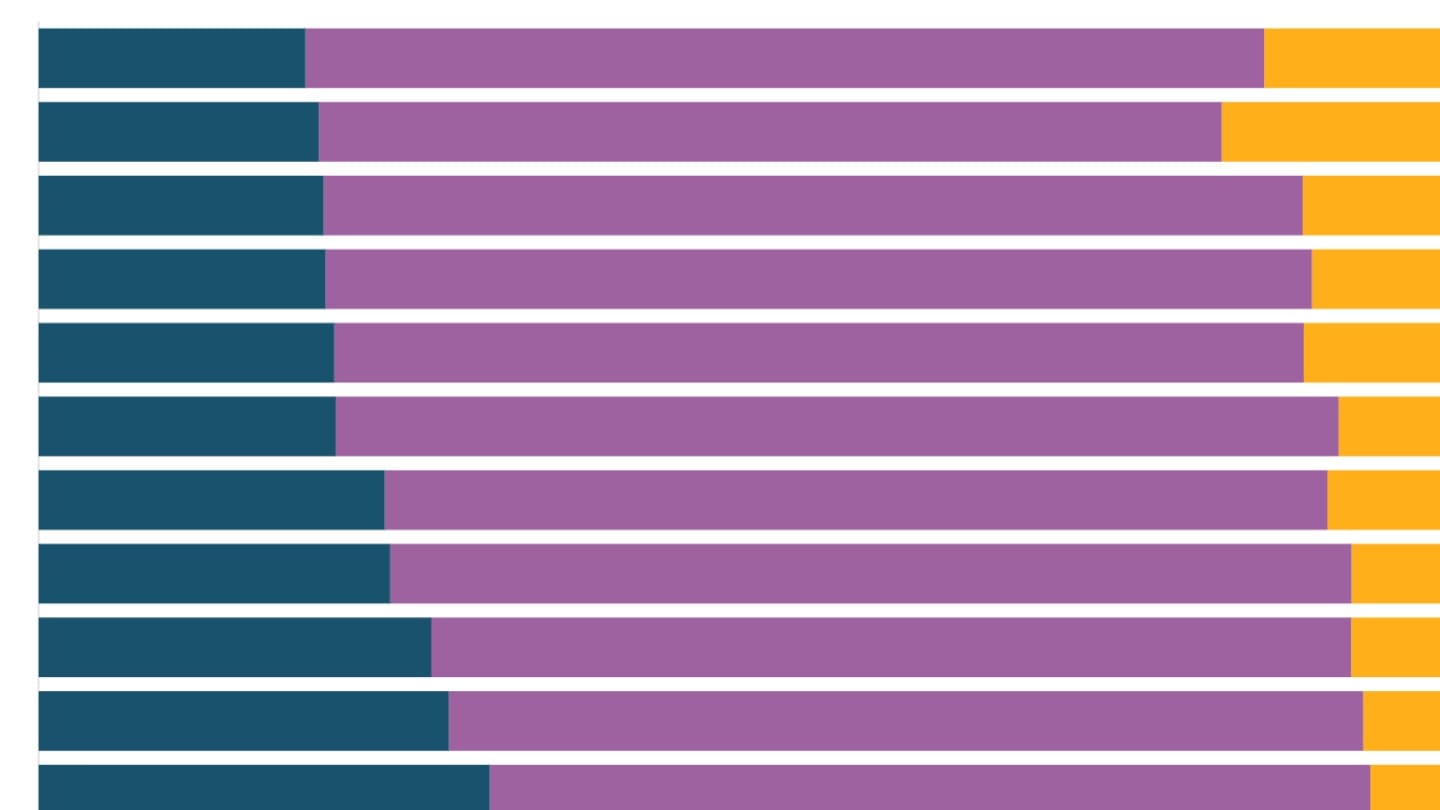

But the risk of dying in infancy and early childhood has fallen dramatically in India over the last 70 years. In the 1950s, more than one in three deaths in India were of infants under the age of one, and more than half of those dying every year were children under the age of five. Deaths in early childhood now account for fewer than one in ten deaths in India.

This has meant that India's Infant Mortality Rate - the number of deaths among children under the age of one for every 1,000 live births in a year, and one of the primary indicators that public health experts look at - has fallen steadily. Over the past 50 years, India's IMR has gone from 134 deaths of children aged less than one for every 1000 live births in 1971 to 25 in 2023.

Although IMR is falling everywhere, poorer regions in India have higher rates of infant mortality. While infant mortality remains higher in rural than in urban areas, this gap has narrowed significantly in the last few decades.

Age-specific death rates

As a result of these large improvements in infant mortality, the relative risk of death in India is shifting to older age groups.

The relative risk of death by age group is an important way to compare different regions. Kerala and Uttar Pradesh, for instance, have similar Crude Death Rates across the overall population, but Kerala's death rate is driven up by the fact that its population is substantially older.

As a result, looking at age-specific death rates (the number of deaths in a particular age group relative to the population in that age group) is a useful way to separate out the effects of age distribution on mortality. Comparing age-specific mortality rates across Indian states shows the disproportionate risks to the very young in India's poorest states, where the risk of dying in infancy remains higher than the risk of dying at older ages.

Life expectancy

As a result, with every passing year, the age to which a child born in that year can expect to live has been going up. This is known as life expectancy, and involves a combination of estimating the current and likely future impact of the socio-economic factors that affect health and mortality.

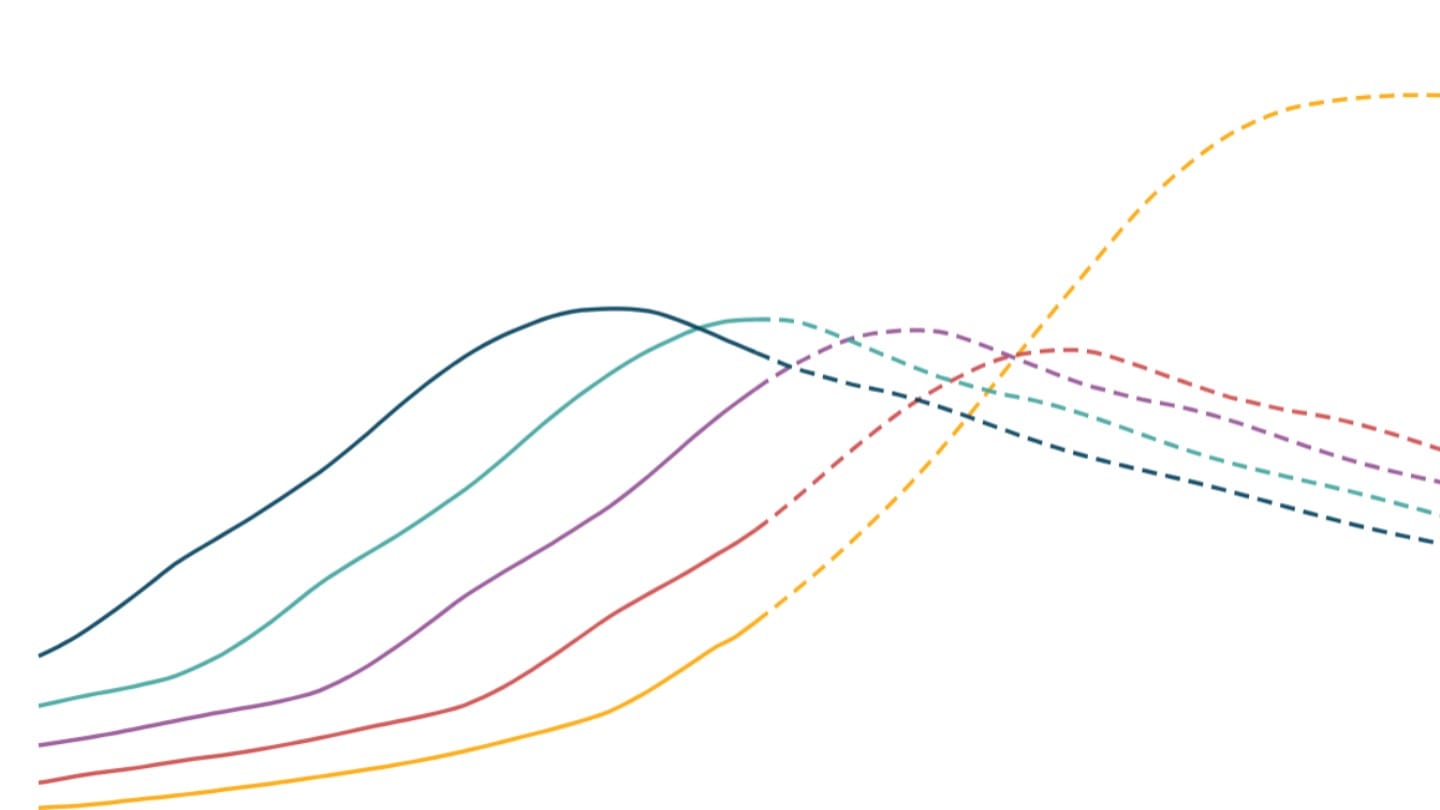

From being under 50 years in 1970, life expectancy in India has grown steadily over time, to over 70. In the 1970s when comparable data was available, Indian men lived longer than women. That male advantage was reversed in the early 1980s, and a girl born in the late 2010s could now expect to live nearly three years longer than a boy born in the same year.[3]

However the expectation of life is not uniform across the country - a child born in Delhi can expect to live nearly ten years longer than a child born in Chhattisgarh today. In most states, there is also a significant urban advantage, and an urban Indian can expect to live three years longer than a child born in rural India.

The future of Indian mortality

Mortality rates and their change over time in a population have to do with two key factors - development and demographics. As countries grow and develop, the risk of dying from communicable diseases like diarrhoea and malaria, particularly in infancy and early childhood, begins to fall. But as countries get better developed and their populations become older on average, mortality rates start to go up again.

UN projections for India[4] indicate that as the country continues to age, the number of deaths every year, as well as mortality rates relative to population have begun to trend up and will continue to do so.

What will be different in the future, however, is that most of these deaths will take place among the elderly rather than among the very young as they did in the past.

Measuring mortality

The most direct way to measure mortality would be if every death was registered, and attended to by a health professional who certified its cause. However in low-income settings like India, this isn't uniformly possible; not all deaths are registered with civil authorities, and the rates of death registration are lower still in poorer states.[5]

To fill in these gaps India has a Sample Registration System which conducts a large, nationally representative sample survey every year in which enumerators visit households, enquire about deaths in the preceding year in that household, and produce estimates of national mortality from that. This is one of the reasons that DFI uses the Sample Registration System to understand mortality - so that we do not miss some deaths because they were not registered.

The SRS began in the 1970s and the most recent year for which SRS data is publicly available is 2023.[6] For historical data as well as future projections, we use the United Nations Population Database. For more on measuring mortality, see this piece in our Measurement vertical.

[1] Indian and UN estimates suggest a significant increase in mortality in 2020 and 2021 on account of the COVID-19 pandemic followed by a recovery to earlier levels.

[2] National Family Health Survey 5th Round (2019-21), International Institute for Population Sciences.

[3] The male disadvantage in life expectancy is a global phenomenon and is attributed to genetic and behavioural factors. In countries with poor female health and high maternal mortality, this trend may be reversed, and reverts to the expected course when female and maternal health improve, as in India: UN World Population Prospects 2022.

[4] World Population Prospects 2024 Revision, United Nations Population Division.

[5] Vital Statistics of India based on the Civil Registration System (2019), Office of the Registrar General of India.

[6] Sample Registration System Statistical Report (2023), Office of the Registrar General of India.