Population projections and their track record

Between censuses, and to plan for the future, countries rely on population projections. Understanding how these projections are made, as well as their past successes and failures, is vital.

Most countries of the world conduct a full count of their population every ten years, typically at the start of each decade. For years in between two censuses, there are population projections or forecasts to track demographic changes.

Businesses use these projections to figure out where demand for certain products might rise or wane. For instance, baby care products would sell more in regions with a fast-growing population. Pension products may sell more in older regions. Policymakers use these projections to allocate funds across regions, and to plan the provision of public facilities. As a result, getting these projections right is vital.

For some developing countries, the UN World Population Prospects (WPP), revised every few years, is the only source of population projections. In India, population projections are also published after each decennial census by a technical committee led by the Registrar General of India (RGI).

How projections are made

Both UN and RGI projections are based on the cohort component model[1], in which the components of population change (fertility, mortality, and net migration) are projected separately for each birth cohort or age-group.[2] The base population (or census count) for each region is adjusted for age-wise mortality rates and migration rates to estimate the surviving population counts for future years. New births are added to the ranks of survivors by applying expected fertility rates to the female population.

The availability and quality of basic demographic data often determines the reliability of these projections. UN projection errors - which we define as the percentage gap between projections and census counts - for India are comparatively low compared to several other large developing nations. In some developing countries such as Nigeria, the national census count (or the base population) itself has been a subject of controversy for many decades now.[3] In other developing countries such as Bangladesh, post-enumeration surveys suggest that the national census counts miss a significant share of the young population.[4]

India's national census counts tend to miss fewer people as post-census surveys show, providing a more reliable base for projections.[5] India also has a long history of producing reliable estimates of fertility and child mortality from other regular surveys.[6]

How short-run projections stack up

Demographic forecasters make both short-run and long-run projections. Short-run projections here refer to projections made five or six years before the next census count.

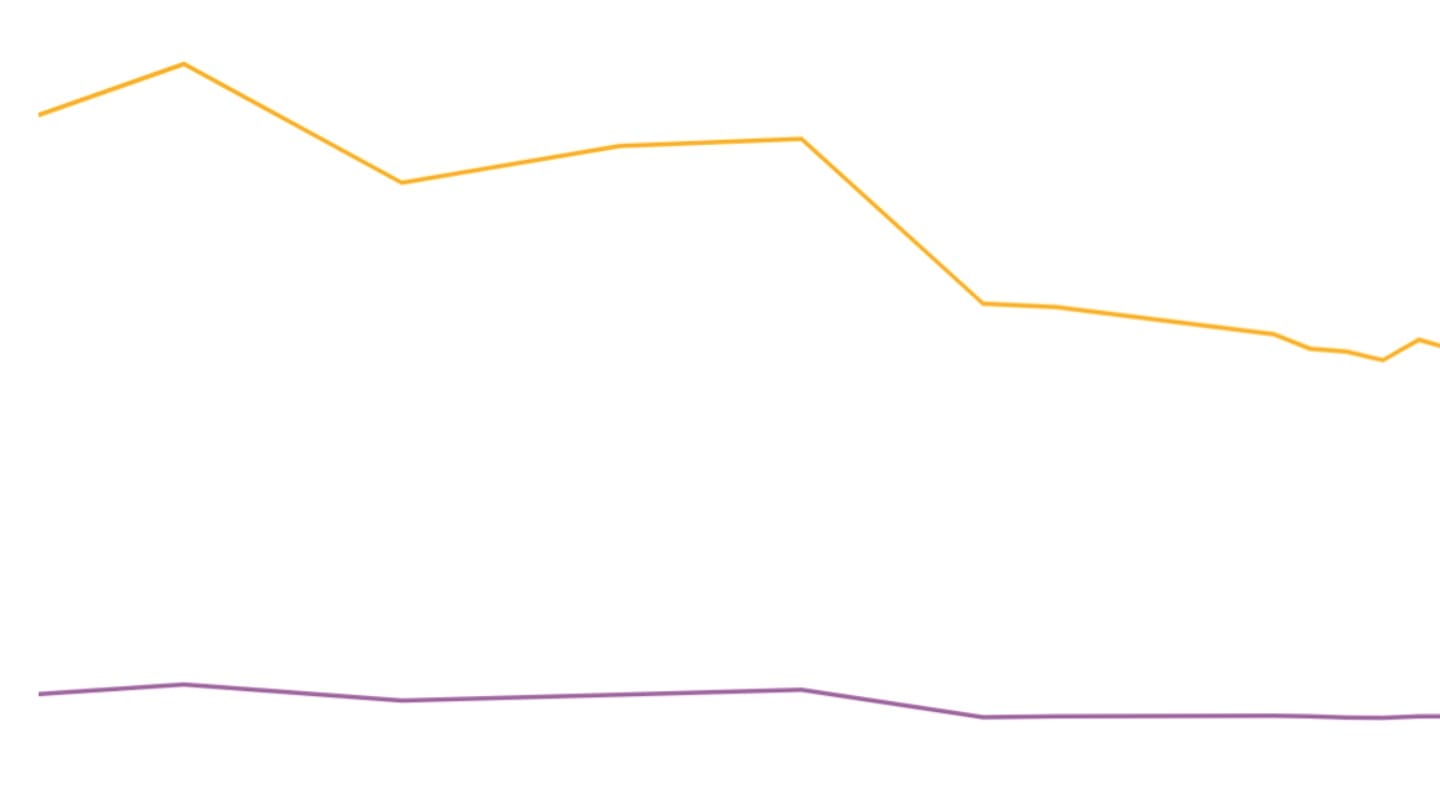

The UN's short-run projections for India have missed the census count by 1 percentage point or less over the past three censuses. The RGI's short-run projections have missed the mark by 1-2 percentage points over the past three censuses at the national level.

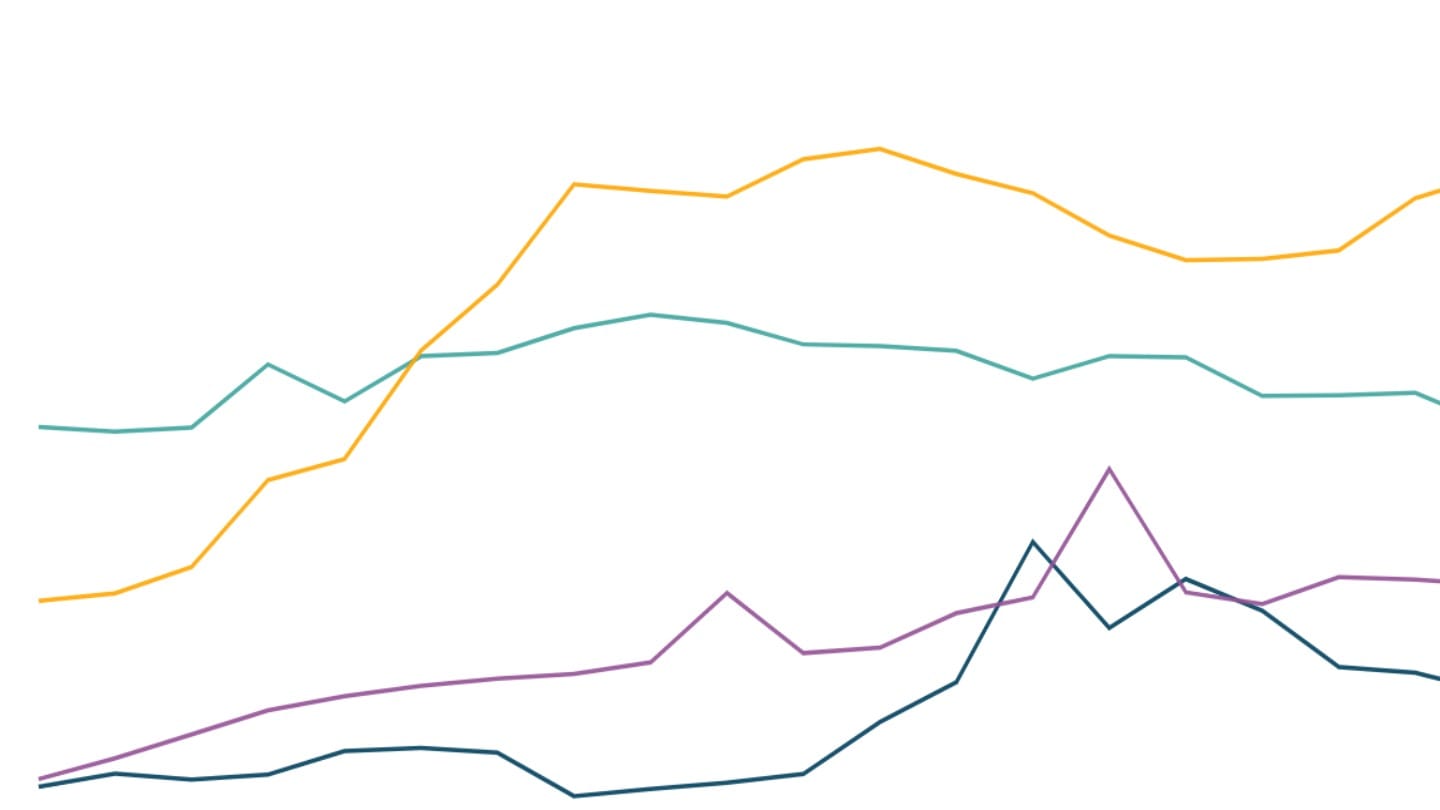

Short-run projection errors differ widely across Indian states. Over the last three censuses, the RGI has substantially under- or over-estimated the populations of several large states in projections made 5-6 years before the census.

The RGI's 2006 population projections, for instance, underestimated the 2011 population count for most of the populous states. Among the 12 most populous states of the country, projection errors were the highest for Tamil Nadu (projection underestimated the actual count by 6.5%) and Bihar (6.1% underestimation).

The RGI also over-estimated the population in its 2006 projections for Andhra Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh, but the margin of error was small. Besides, past projections for these states were underestimates, suggesting that the RGI projections for these states were not systematically biased in one direction.

The big outlier in the RGI's projections has been Kerala, a state whose population it has systematically and substantially overestimated since the 1980s.

There is no independent research yet on the reasons behind RGI's hits and misses over the past few decades.

The shaky record of long-run projections

On balance, population projections do a decent job of predicting short-term population trajectories. Long-range projections tend to have a poorer record. This is true of both UN and RGI projections. Errors for projections 15 years ahead are higher than for short-run projections.

Population projections for 50-year or 70-year horizons tend to perform even more poorly.[7] This is because population projection models rely heavily on recent trends in fertility and mortality. Over the long run, these trends change considerably. Long-run trends in fertility[8] and mortality[9] are impacted by a wide range of factors , including investments in public health, economic growth, and changes in educational attainments.[10] Unless accurate predictions are available for these parameters, it is impossible to correctly estimate demographic parameters over the long run.

Projections for India currently rest on particularly shaky ground. India's last census was due to be conducted in 2021, but has not yet got off the ground. As a result, the base data on which the UN makes predictions is significantly out of date. The RGI's projections, meant only to bridge the gap between 2011 and 2021, are still in use in the absence of actual census data. Without updated census data, the risk of a wide gap between projections and reality will only grow.

[1] Methods for Population Projections by Age and Sex (1956), Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations

[2] Population projections by the RGI use the component method for five-year age-groups while the UN World Population Prospects use single-year age bands.

[3] The Nigerian Census: Problems and Prospects (1999), The American Statistician

[4] A post-enumeration check conducted by the Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies, an independent organization, assessed the accuracy of Census 2011 and identified a net undercount of 3.97%, an improvement from the 4.98% undercount recorded in the 2001 Census.

[5] A post enumeration survey conducted by the RGI after the 2011 census showed that it had missed 2.3% of the population.

[6] The Sample Registration System (SRS) was initiated by the RGI in the 1960s to collect demographic data on a regular basis since most births and deaths in the country were not registered. Independent estimates of fertility and child mortality are now also available from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS).

[7] In 2019, the United Nations projected that the global population would exceed 10.9 billion by 2100 and continue growing into the 22nd century. However, by 2022, this forecast shifted significantly, predicting a peak of 10.4 billion in the 2080s, followed by a gradual decline.

[8] Determinants and Consequences of High Fertility: A Synopsis of the Evidence (2010), World Bank

[9] A Systematic Review of Sociodemographic, Macroeconomic, and Health Resources Factors on Life Expectancy (2021), Asia Pacific Journal of Public Health

[10] Effects of education on adult mortality: a global systematic review and meta-analysis (2024), Lancet Public Health