The move away from agriculture

As countries industrialise and grow, the contribution of agriculture to the economy starts to fall. But the pathways from there on are diverse, and India is in some ways unique.

In one key way, India is still an agrarian country. Of the three key sectors that the economy of a country is divided into - agriculture, industry and services - agriculture still employs the largest share of Indian workers. However, its contribution to the economy has been falling over time, while the share of services has risen significantly.

The falling share of agriculture

Historically, as countries have industrialised, the contribution of agriculture to their economies has steadily fallen.

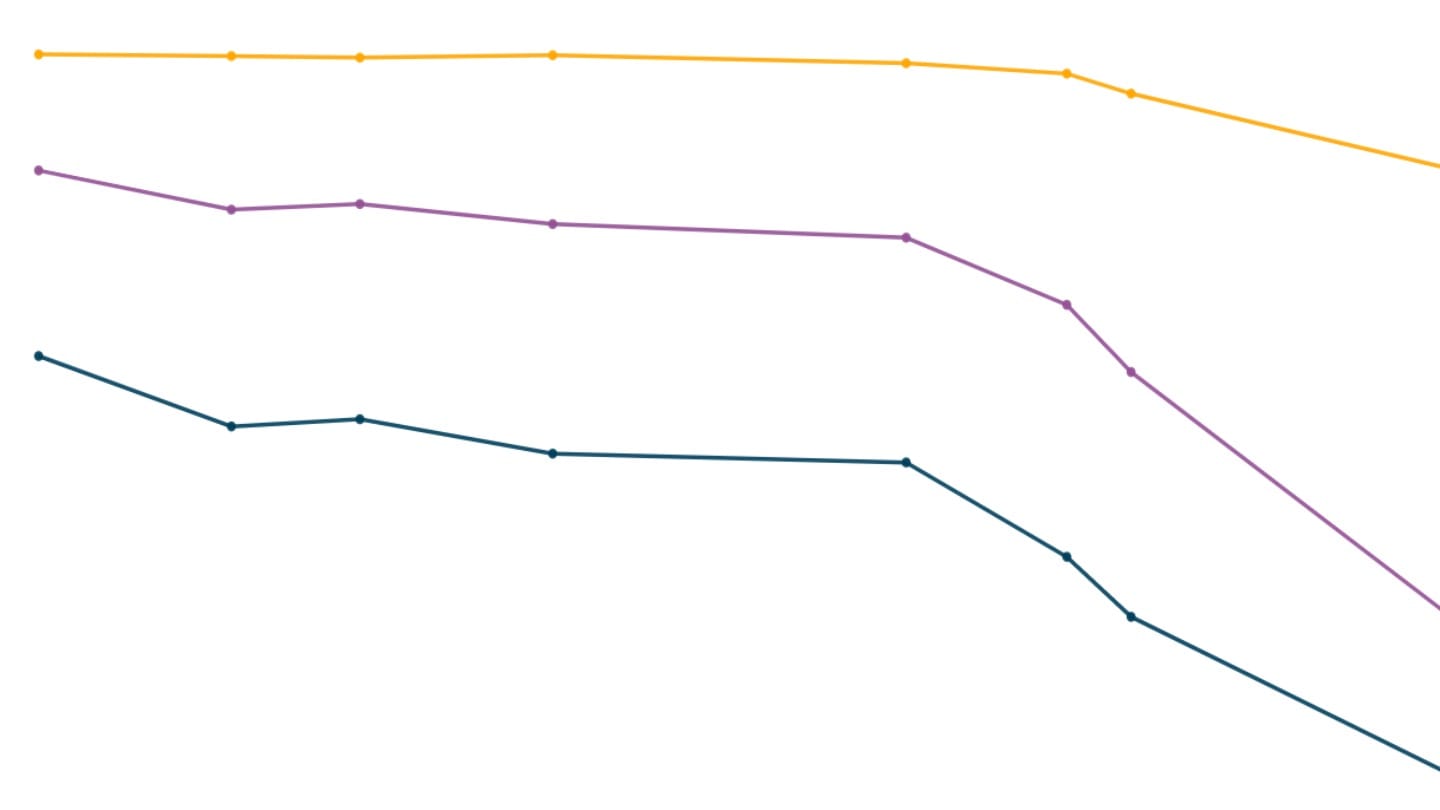

On this count, India is on a similar trajectory. In the 1970s, agriculture was the single biggest contributor to the Indian economy of the three sectors, accounting for 40% of Gross Value Added[1]. Today, agriculture accounts for less than a fifth of the economic output.

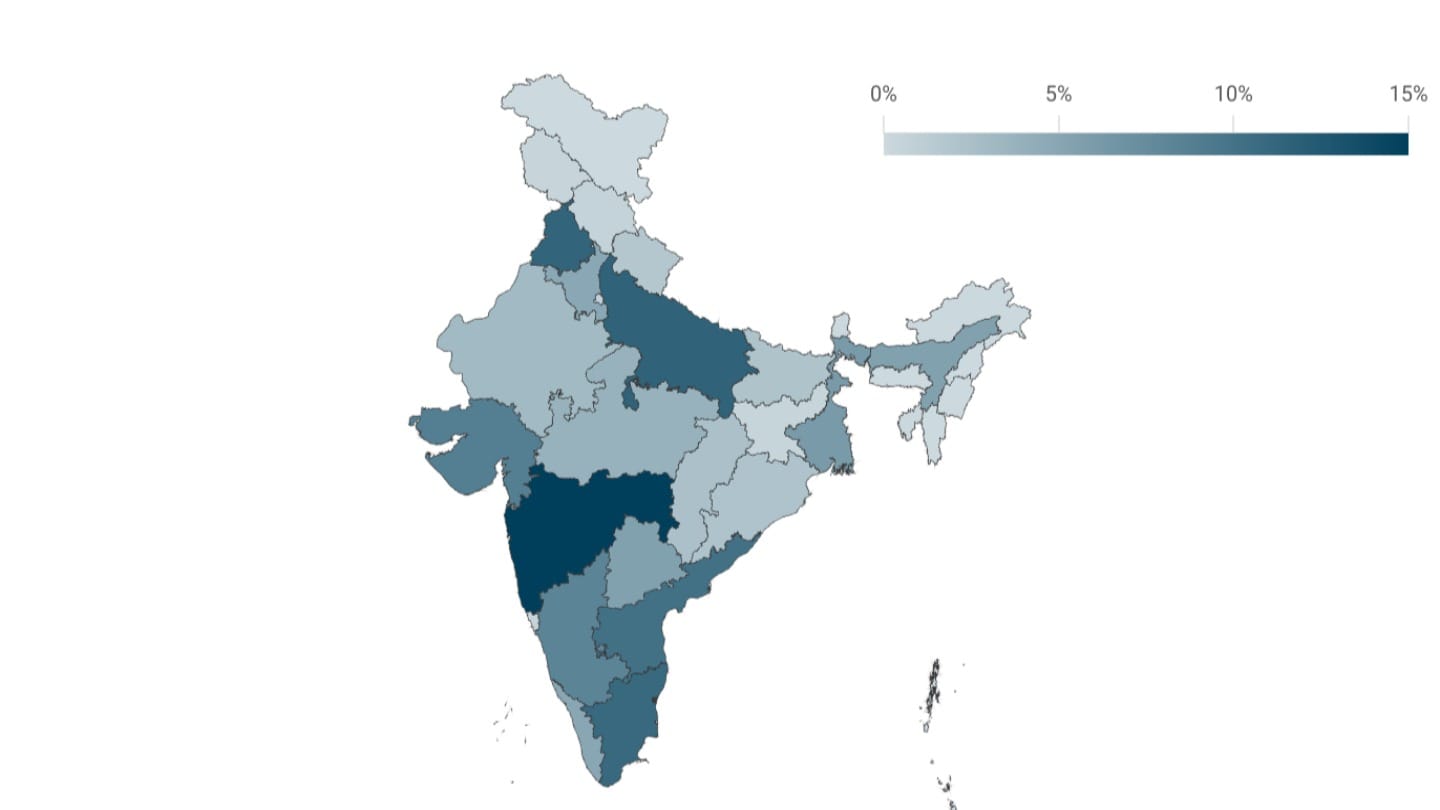

But the share of workers that agriculture employs has not fallen as sharply as its share in the economy has. In the 1970s, about three-fourths of India's workers were engaged in agriculture. Today, the share of agriculture is down to less than half, smaller than fifty years ago, but still the highest among all major sectors[2]. Rural men moved out of agriculture at a faster pace than rural women.

What this means is that the half of India's workforce that is in agriculture generates only one fifth of the value added in the economy, while the third of the workforce that is in services generates nearly half of national economic value.

Manufacturing stagnation

The paths that countries take once they industrialise are more diverse. For the early industrialisers of Europe and North America, as well as Japan and some of the East Asian economies later, the path was of moving from an agrarian economy to one with a rising share of industry in their economies for several decades, and then a much later growth in services.

In India and some of its peers, on the other hand, that shift has come much earlier, with the contribution of manufacturing in particular peaking early[3].

Since the 1970s, the share of industry in the economy has grown only slightly even while the share of the workforce that is employed by industry doubled[4]. Industry is composed chiefly of manufacturing and construction, with mining and utilities being smaller components.

While manufacturing is the largest component of industry in India in terms of value added to the economy, it is now in decline, having hit its peak in the 1980s. This is substantially different from the trajectory of Bangladesh, for instance, where the manufacturing boom continues to drive growth.

The engine of growth within industry in India has not been manufacturing, but construction. The share of the construction industry in national gross value added has doubled in fifty years. Construction added roughly 60 million jobs in the last five decades; more than one in ten Indian workers is a construction worker[5].

The services boom

The majority of the value added in the Indian economy now comes from the services sector, even as the sector employs less than a third of the workforce.

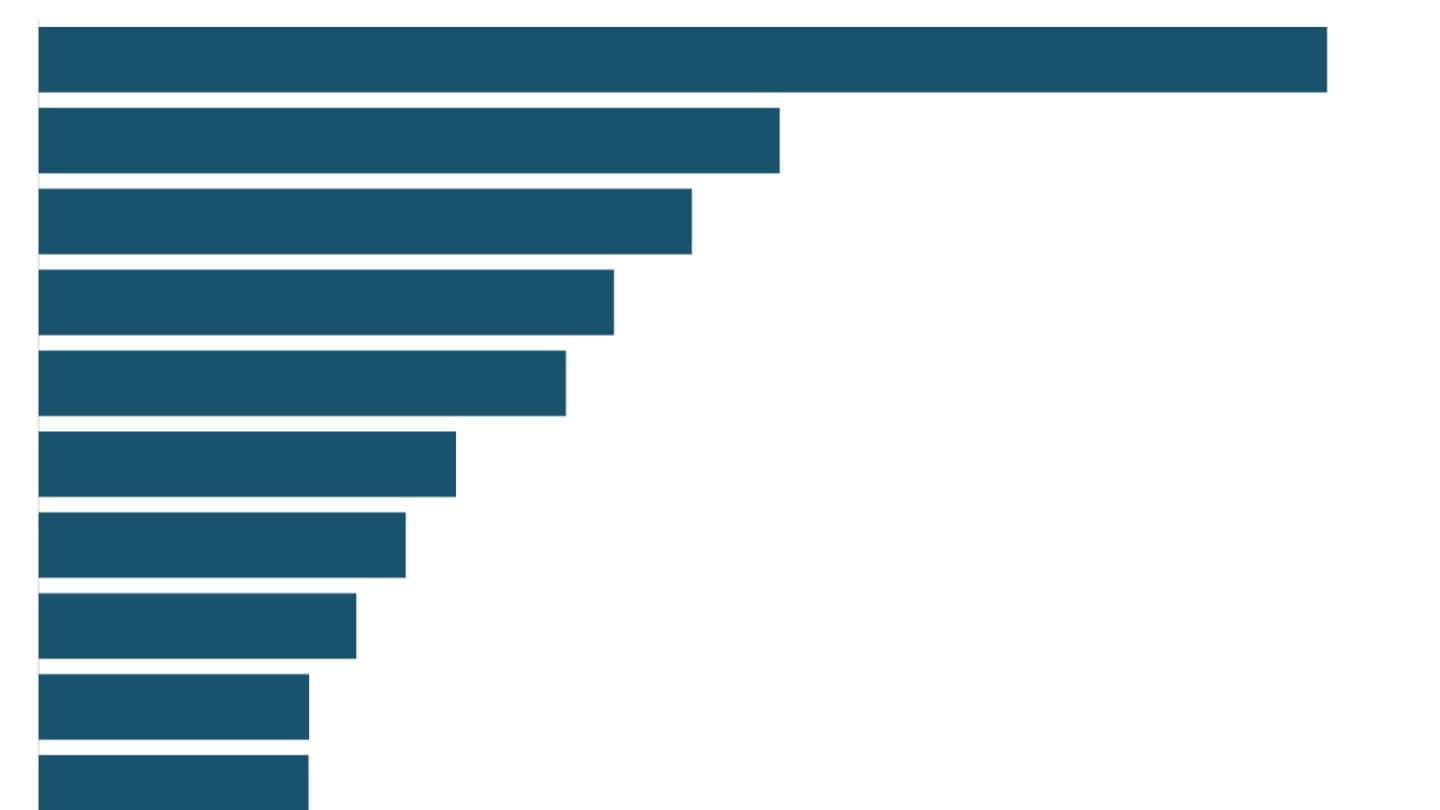

India's services boom was driven primarily by trade and hospitality from the 1970s to the 2000s. Trade and hotels (includes repair services and restaurants), and transport and communications (includes storage and broadcasting) have a 17% share in both the economic value added and in the workforce in services.

In recent decades, however, the services boom has been powered by services other than these, which contribute to a third of the national economic output, despite employing just an eighth of the workforce.

Four key sub sectors under "other services" in particular produce relatively few jobs but have a significant economic contribution. Together, real estate, finance, professional services and public administration employ only 6% of the national workforce, but contribute 28% to India's economy[6].

Real estate, for instance, has a 0.2% share in India's employment. But it contributes 7% to the gross value added in the economy. Financial services, which includes banking, insurance, and investment services, employ 1% of the workforce but contribute 6% to the economy.

The services boom of the last few years has been led, to a large extent, by professional services. These include information technology, legal and accounting services among others.

India in context

Similar to India, services contribute to around half of economic output in emerging economies like China, Bangladesh and Vietnam. However where they differ is in the relative contribution of agriculture and industry. China has been the fastest among these to reduce the imprint of agriculture on employment and the economy. The contribution of industry to India's economy, meanwhile, is relatively low.

[1] The Gross Value Added is the value of all goods and services produced in the country. To measure the GVA, a country must measure the volume of output in all sectors and sub-sectors and multiply it by prices to get the value added. The value of inputs and intermediate goods is subtracted.

[2] Data on employment comes from the Employment Unemployment Surveys (EUS) from 1973 to 2012 and the Periodic Labour Force Surveys (PLFS) from 2017 to 2024 from the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO).

Although there is a broad move away from agriculture to industry and services within India's workforce over the longer term, PLFS data shows that agricultural employment in India has increased in the last few years.

[3] The economist Dani Rodrik of Harvard University finds that countries like India are reaching peak industrialisation in terms of employment and output at much lower levels of income compared to the early industrialisers. Industrialisation peaked in Western European countries such as Britain, Sweden, and Italy at income levels of around $14,000 per capita (in 1990 dollars), while India and many Sub‐Saharan African countries appear to have already reached their peak manufacturing employment shares at income levels of $700 per capita. Rodrik called this "premature deindustrialisation" in his 2015 paper and suggests that it has potentially important economic and political implications.

[4] Gross Value Added, or GVA, is how the GDP is calculated using the production approach. Technically, GVA plus subsidies on products minus indirect taxes gives the GDP.

[5] Total population estimates come from the closest possible Census population estimates. For instance, to use data from EUS 1978 (NSS Round 32), the average of the 1971 and 1981 populations is used. For recent years, it has been calculated using population estimates from the official projections by the Registrar General of India for the same year.

The absolute number of workers has been calculated using the work participation rates (WPR) from Employment Unemployment Surveys (EUS) and PLFS and applying them to the total population.

The absolute number of workers in construction is then obtained by applying the share of workers by sector.

[6] Data pertains to 2021-22. Economic contribution is obtained from detailed national accounts statistics, and employment from Periodic Labour Force Survey.