Women and work in India

Many women are out of India's paid workforce. But they're working - just not in the same ways as men.

How many women are outside the workforce, what keeps them out, and what do women in the paid workforce do?

Women out of the labour force

India's labour statistics come from a series of large, nationally representative household surveys on employment that the Indian government has been conducting for over 70 years, while international data comes from the International Labour Organisation.[1] (For more on measuring employment, see this piece in our Measurement vertical.)

India has an estimated 520 million women and 540 million men[2] over the age of 14 who can legally work.[3] Not all adults who are of legal working age work - old age, disability and other factors typically keep some adults out of the labour force in most countries. But there is also a distinctly gendered dimension to who is in the labour force.

The labour force is made up of people who are either working (employed) or looking for work (unemployed). The rest are considered to be out of the labour force, meaning that they are of legal working age but do not participate in the paid workforce.

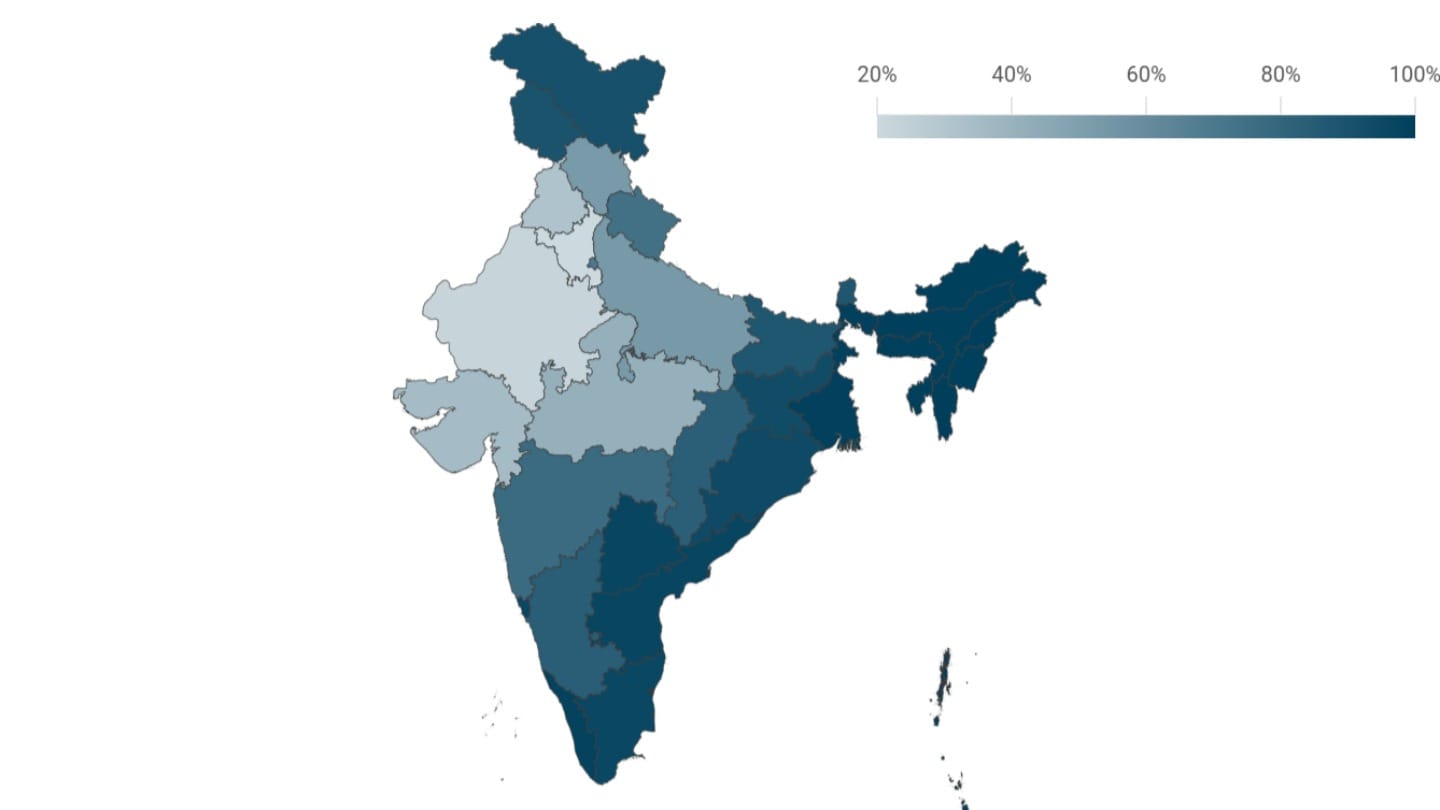

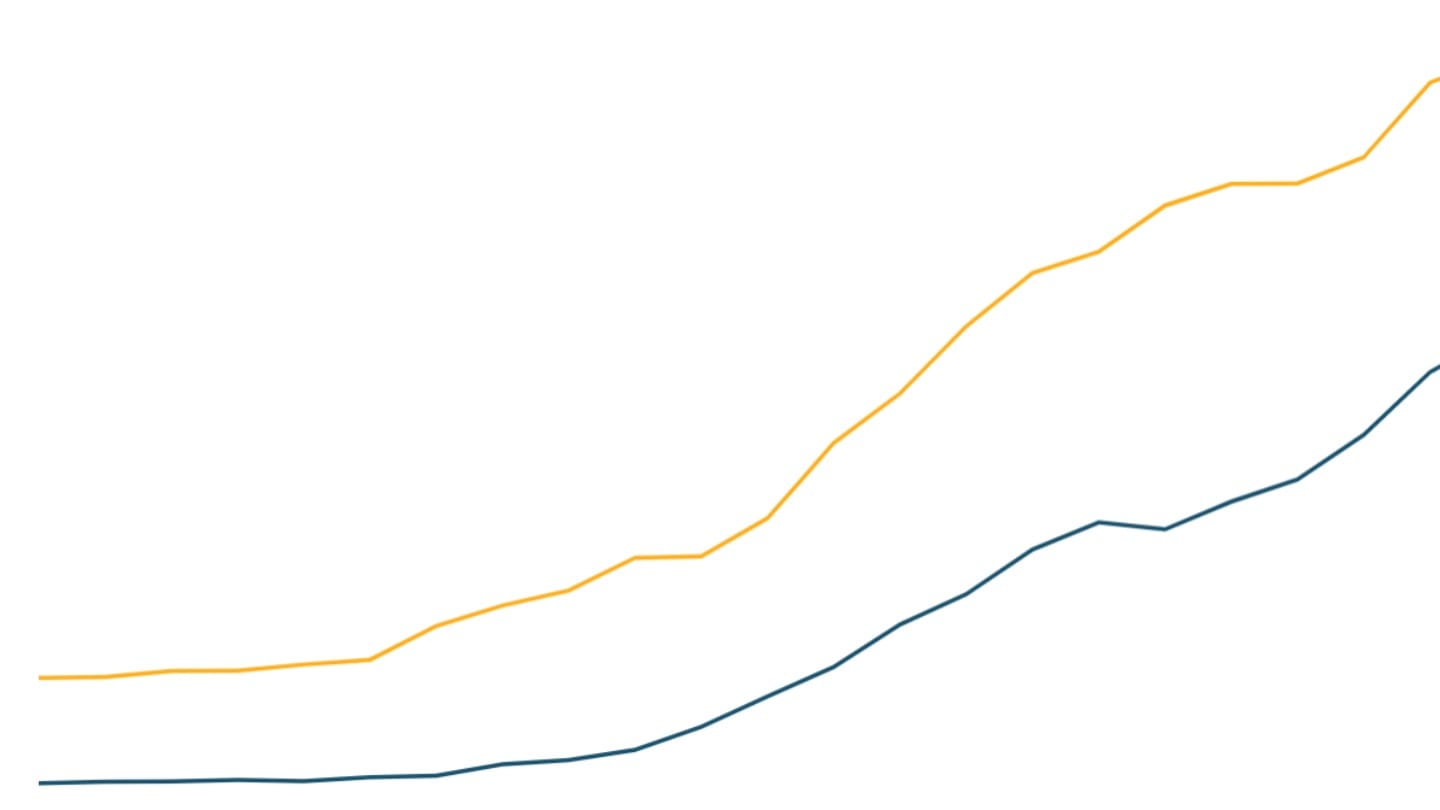

India's most recent labour statistics[4] show that while eight in ten men are in the labour force, only four in ten women are. India's female labour force participation rate (people who are either working or looking for work as a share of the population) is lower than in many countries at comparable levels of income and development, although it has seen an improvement in recent years.[5]

As a result, women are significantly underrepresented in India's labour force. India has an estimated 625 million-strong labour force out of which, a little more than 215 million are women. The gender balance in the urban labour market is even more skewed. Urban India, where 500 million people live, has less than 50 million women in the labour force.

Working - but in the home

Women who are not in the labour force are still working, but in a way that is different from how work is understood in economics.

In economics, "work" covers activities that produce an output which is either consumed by the household or is sold in the market for a price. In Indian and international labour statistics, activities that produce goods for self-use and sale are considered as work. So a farmer growing vegetables for the household to eat constitutes work, as does her selling those vegetables in the market.

But in terms of services, only those activities that produce an output which can be sold are considered work.[6] So transporting the harvested vegetables to the market for sale is work, but cooking those vegetables for the household members to eat, or the feeding of small children is not considered work.

This unpaid care and domestic work is mostly performed by women. Whether this unpaid care work should be counted as productive work is a widely debated topic in labour economics both in India and globally.[7]

Of the estimated 120 million men out of the labour force, the majority are in higher studies, while of the 300 million women who are out of the labour force, most are attending to "child care and personal commitments in home-making".[8]

Staying out of the labour force is not associated only with poorer women, rural women or those with lower levels of education. In fact, women who are graduates or have higher education degrees are more likely to be out of the labour force and attending to domestic responsibilities than women with no education.

Women in the workforce

Of the roughly 420 million men and 215 million women in the labour force, about 13 million men and 7 million women are unemployed. The rest make up what is called the workforce.

This translates to an estimate of a little over 400 million men and 200 million women in India's workforce. But the nature of work among women workers is also materially different from the work that men do.

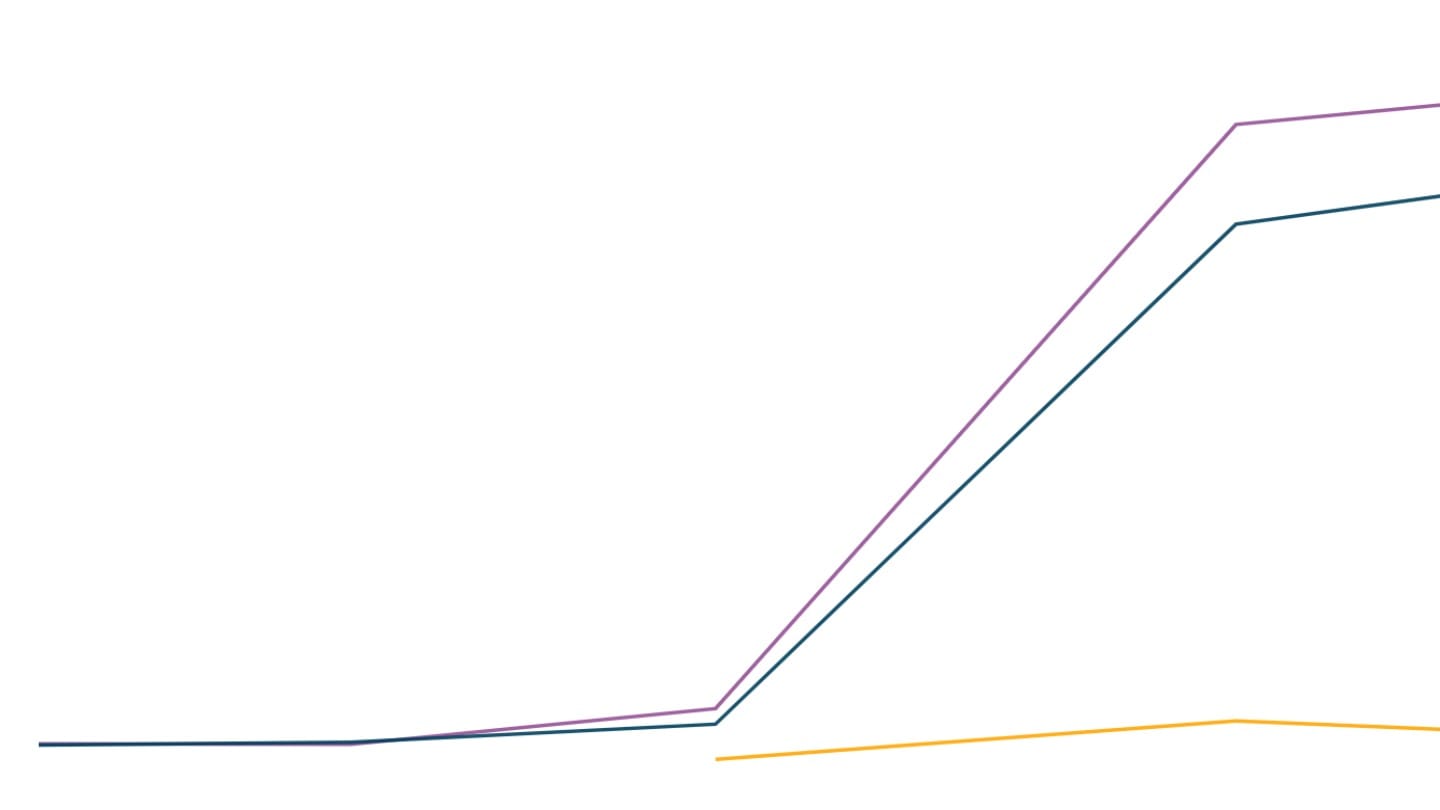

More than one in three working women - or 70 million women - are doing economically productive work, but for no wages. These are women who work in a household enterprise that is engaged in crop cultivation, milk and livestock production, retail sale of food, or small-scale manufacturing, but do not get paid for their work. In Indian labour statistics, they are termed as "unpaid helpers in household enterprises." While some men do such unpaid work as well, women are twice as likely to be unpaid helpers.

In comparison, less than half as many women are in salaried work.

For both rural men and women, farming is the chief occupation. But there are differences - all of the top five occupations for rural women are related to agriculture, and they cover three quarters of working women. On the other hand, construction workers and shopkeepers are key occupations among rural men.

In urban areas, shopkeeping or selling items in retail shops is the most common occupation for men. Driving vehicles and working at construction sites are common jobs at lower levels of education, while managerial and technology roles like software development are the top occupations as education levels rise among urban men.

The top occupations for urban women that both employ more than one in ten working women are garment work such as tailoring and that of cleaners and helpers in homes, hotels and offices. As education levels rise, tailoring and other jobs in garment factories feature above domestic help jobs. Higher educated urban women are most likely to work as teachers.

[1] From 1972 to 2012, India's Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation carried out large, nationally representative household surveys called the Employment and Unemployment surveys roughly every five years. Since 2017-18, India has switched over to the Periodic Labour Force Surveys which track the size and characteristics of India's labour market every year by surveying more than 400,000 people in one annual cycle. The International Labour Organisation uses Indian government data and does some modelling for international comparisons. DFI uses these three data sources.

[2] National employment surveys such as the Periodic Labour Force Survey produce ratios such as the labour force participation rate and the unemployment rate. To produce absolute numbers, DFI uses population projections from the National Commission on Population (based on the 2011 Census)).

[3] India is signatory to International Labour Organisation conventions that bar children under the age of 14 from working. References to "men" and "women" in this piece refer to those over the age of 14

[4] Periodic Labour Force Survey 2023-24

[5] For international comparisons, we use International Labour Organisation data which measures the labour force participation for countries by looking at a reference period of one week ("current weekly status"). For national estimates using the PLFS we use a reference period of one year ("usual status"). There are slight differences in data depending on the measure used.

Additionally, the ILO data uses the calendar year, while national estimates for India follow the survey year that runs from July to the June of next year.

[6] This definition follows from the System of National Accounts (2008), an internationally accepted statistical framework that is also used to define labour force and employment in employment surveys from the National Sample Survey Office.

[7] See work on this topic by ILO, OECD and UN Women

[8] The Periodic Labour Force Survey 2023-24 asks respondents their "main reason for being out of the labour force"